Dawn on January 30, 1942, found Admiral Giffen's Task Force 18 on its way back to Espiritu Santo. Their mission had not been completed. They did not rendezvous with the destroyer division from Tulagi, as had been planned. The resupply ships unloaded their supplies on Guadalcanal without the protection of TF 18.

Apparently Giffen lifted radio silence, because the previous night's disaster was reported to Adm Halsey in Noumea. At Halsey's direction, the two escort carriers kept a combat air patrol (CAP) on station over Chicago and Louisville all night long. He also ordered Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman's Enterprise carrier group to dd more CAP aircraft from dawn to dusk.

Halsey dispatched the tug Navajo and the destroyer transport Sands to go to Chicago's assistance. That afternoon, Halsey directed Giffen to return to Efate with the remaining battle worthy ships, turn the towing duties over to Navajo and rely on CAP to defend Chicago. Giffen took with him on Wichita the force's only trained fighter direction officer (FDO). Chicago had no practical way to control the CAP sent to their defense.

Four Grumman F4F's from Enterprise spotted a Japanes scout bomber and chased it for 40 miles, leaving Chicago unprotected. Eleven Japanese Bettys appeared over the horizon.

USS Enterprise, now only 40 miles south of Chicago, directed a flight of six F4F's to intercept the bombers, which appeared headed for Enterprise. The Japanese bombers immediately reversed course and headed for Chicago, which they believed to be a battleship. They identified the destroyer La Vallette, still standing by the cruiser and tug as a "Honolulu-class" cruiser. About 4:20 pm, nine Japanese bombers appeared out of the clouds and made their final approach in the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire.

At 4:24 one torpedo hit the starboard side forward, followed almost immediately with three torpedoes right where the ship had been hit the previous day. The captain ordered "abandon ship." At 4:43 pm the ship rolled to starboard and sank with her colors flying.

Navajo, Waller, Edwards and Sands picked up 1,069 survivors. La Vallette took one torpedo hit and survived.

Admiral Nimitz was irate when he learned that Chicago had been lost. He blamed Admiral Giffen. Giffens career survived, however, and he retired after the war as a Vice Admiral.

Chicago lost six officers and 55 enlisted men when the ship went down.

Chicago was the last ship lost in the struggle for Guadalcanal. By February 9, Japan had evacuated their last soldiers from the island.

This may have been the final "turning point" of the war. After this, Japan was fighting a rear guard action. The United States was busy replacing their lost ships, planes and sailors. Japan was not able to.

The cost of victory was high. For 2500 square miles

of jungle, tall grass and sluggish rivers, the Allies had lost two fleet carriers,

eight cruisers, 14 destroyers, numerous smaller vessels and aircraft, and over 6,000 lives:

nearly 1600 Marines and soldiers, the rest - three times as many - Navy officers

and men.

The cost of defeat was higher. Japan lost two battleships, a small carrier,

four cruisers, 11 destroyers, and more than 23,000 men.

But they also lost any hope of victory.

Showing posts with label military. Show all posts

Showing posts with label military. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: Battle Of Rennell Island

The first six months of the war in the Pacific were fought mostly with ships, planes and men already in the Pacific when Pearl Harbor was attacked. They had been worked up to a high state of combat readiness by their fleet commander, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. Even after Kimmel was relieved of duty following the attack, the surviving forces acquitted themselves well.

The Pacific Fleet was hard pressed. They had lost four of their six large aircraft carriers in combat, and the remaining two, USS Saratoga and USS Enterprise, were just returning from extensive repair.

Some Pacific Fleet assets had been diverted to the Atlantic for the invasion of North Africa. That invasion now over, ships were moving through the Panama Canal to reinforce the Pacific.

That was the good news. The bad news is that the ships, their officers and their admirals weren't accustomed to operating in the Pacific. Not only was the tactical challenge different from the Atlantic, there was a less tangible difference of attitude.

The Atlantic Fleet was a "spit and polish" outfit. The Pacific Fleet was more a "get the job done" operation. That was especially true of the aviators and submariners.

| RADM Giffen's Formation |

RADM Robert C. "Ike" Giffen, a favorite of Atlantic Fleet Commander Admiral King, had just arrived in the Southwest Pacific with heavy cruiser USS Wichita and escort carriers Chenango and Suwanee, all having just completed the invasion of North Africa.

Giffen had experience against German submarines, but none against Japanese naval air forces. He also had very limited experience operating aircraft carriers. The two escort carriers were slow. Converted oilers, they could make no more than 18 knots. Worse than that, the wind was from the southeast, opposite from the direction Giffen needed to go.

Giffen had no concept of Japanese naval skills at operating both warships and aircraft at night.

Giffen's task force of three heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, eight destroyers and two escort carriers left Efate January 29. Destination: Guadalcanal by way of Rennell Island. Mission: Support a four-ship resupply mission for the marines, then sweep up through the "slot" to find and destroy Japanese ships.

Giffen ordered radio silence. Japanese submarines and aircraft tracked the force from the time it left Efate.

|

| Louisville Towing Chicago |

Under the circumstances, strict radio silence made little sense. The ships used their air and surface search radars, which the Japanese could detect at about the same range as the UHF radios used for line of sight communications. Most importantly, this order prevented the cruisers from communicating with the aircraft launched by the carriers.

Early the afternoon of January 29, Giffen worried that he wouldn't be at his rendezvous point on time. He ordered the two carriers, along with two destroyers, to continue at best speed, while the remainder of his force increased speed to 24 knots, remaining in a formation designed to protect against submarines rather than aircraft attack. Steaming at that speed increased the force's self noise so greatly as to render the sonar used to detect submarines nearly useless. It also announced the presence of the task force out to almost as great a distance as UHF radios would have.

Shortly after increasing speed, radar operators on the cruisers began picking up radar blips of unidentified aircraft ("bogies"). The US radars were equipped with an IFF feature to electronically distinguish friend from foe, but operators deemed it unreliable. To find out whether the radar blips were friendly or hostile aircraft would have required fighter-director personnel to send aircraft from the carriers to visually identify the aircraft. But they couldn't do so because of radio silence.

Radio silence made no sense.

At sunset, Giffen ceased zigzagging his force and proceeded on a set course to his rendezvous. The bogies were about sixty miles to the west, approaching fast. They were in fact hostile, Japanese twin-engine land-based bombers, armed with torpedoes. The Bettys maneuvered around Giffen's force and attacked from the east, where they sky was dark, but with Giffen's ships silhouetted against the evening twilight.

Giffen's ships put up a barrage of anti-aircraft fire, and the first wave of bombers did not damage any of the ships. USS Louisville was struck by a dud torpedo, but there was no damage. Giffen issued no orders, and the force continued as before.

A second Japanese air group dropped flares alongside Giffen's cruisers in the moonless night. At 7:38 pm, the lead Betty crashed in flames off USS Chicago's port bow, brightly silhouetting the ship for the following aircraft.

One air launched torpedo hit Chicago in the starboard side, flooding the after fire room. Two minutes later, another torpedo hit at number three fireroom. Three of the ship's four shafts stopped turning, the rudder jammed, and soon the ship was dead in the water. Another torpedo hit the flagship Wichita but did not explode.

Chicago's crew managed to control flooding with the list at 11 degrees. At first, they had only electrical power from the emergency diesel generator. Soon they were able to relight one boiler and generate more electricity to use more powerful pumps.

Giffen ordered USS Louisville to take Chicago in tow. By midnight, The tow was underway at three knots, headed for Espiritu Santo.

Friday, January 25, 2013

Should We Worry About Wind Farms And The Marines?

Today's County Compass reports a brouhaha resulting from a request by representatives of Cherry Point MCAS to appear before a joint session of the Pamlico County Board of Commissioners to discuss wind farms. Commissioner Delamar, who has supported wind farms in Pamlico County, voted against the meeting. His was the only vote against it.

I plan to attend the meeting. I hope to hear from the Cherry Point representatives an informative discussion examining potential problems, including a technical explanation, along with proposed solutions. I want to see some empirical data backed by research. I would hope that an expert from NRL might appear. If the proposed solution is not to have wind farms in Pamlico County, I will be very disappointed.

One commissioner is quoted as saying "the Marine Corps deserve our respect just based on who they are." I share that commissioner's high regard for the marines. At the same time, I would hope that our marines are bending every effort to insure that we can share the land, sea and air space of Eastern North Carolina without precluding other future economic development in the region.

By the way, we should all recognize that effective alternate energy sources to replace the burning of fossil fuels is an urgent national security priority. In fact, the Department of the Navy (including the marines) has taken the lead in DOD in fostering alternate energy development.

I gather that the marines share a concern of a number of government agencies that wind farms present a particular challenge to radars, including air search and air control radars, including doppler radars for meteorology. The fundamental concern is radar clutter.

Clutter has been a major challenge for radar designers from the earliest days. Dealing with clutter has generated an alphabet soup of anti-clutter measures: STC, AGC, FTC, IAGC, MTI, frequency agility, circular polarization, Moving Target Detector, Pulse-Doppler Systems, and on and on. Clutter presents some of the same challenges as are presented by electronic and mechanical jamming.

Solving particular problems of clutter from wind farms may not be trivial, but is certainly surmountable.

The following is an executive summary of a 2008 report by The MITRE Corporation, one of our premier defense contractors with experience in this area.

Wind Farms And Radar

January 2008

The MITRE Corporation

1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

"Wind farms interfere with radar. This interference has led the FAA,

the DHS, and the DOD to contest many proposed wind turbines in the line

of sight of radar, stalling development of several thousands of MW of wind

energy. A large number of such denials is a serious impediment to the nation’s

mandated growth of sustainable energy.

"There is no fundamental physical constraint that prohibits the accu-

rate detection of aircraft and weather patterns around wind farms. On the

other hand, the nation’s aging long range radar infrastructure significantly

increases the challenge of distinguishing wind farm signatures from airplanes

or weather.

"Progress forward requires the development of mitigation measures, and

quantitative evaluation tools and metrics to determine when a wind farm

poses a sufficient threat to a radar installation for corrective action to be

taken. Mitigation measures may include modifications to wind farms (such

as methods to reduce radar cross section; and telemetry from wind farms to

radar), as well as modifications to radar (such as improvements in processing;

radar design modifications; radar replacement; and the use of gap fillers in

radar coverage).

"There is great potential for the mitigation procedures, though there

is currently no source of funding to test how proposed mitigations work in

practice. In general, the government and industry should cooperate to find

methods for funding studies of technical mitigations. NOAA has an excellent

research plan, but no adequate funding to carry it out.

"Once the potential for different mitigations are understood, we see no

scientific hurdle for constructing regulations that are technically based and

simple to understand and implement, with a single government entity tak-

ing responsibility for overseeing the process. In individual cases, the best

solution might be to replace the aging radar station with modern and flexi-

ble equipment that is more able to separate wind farm clutter from aircraft.

This is a win-win situation for national security, both improving our radar

infrastructure and promoting the growth of sustainable energy.

"Regulatory changes for air traffic could make considerable impact on

the problem. For example, the government could consider mandating that

the air space up to some reasonable altitude above an air-security radar

with potential turbine interference be a controlled space, with transponders

required for all aircraft flying in that space. This would both solve the

problem of radar interference over critical wind farms and would provide a

direct way to identify bad actors, flying without transponders.

"Current circumstances provide an interesting opportunity for improving

the aging radar infrastructure of the United States, by replacing radar that

inhibits the growth of wind farms with new, more flexible and more capable

systems, especially digital radar hardware and modern computing power.

Such improvements could significantly increase the security of U.S. airspace."

For what it's worth, in my opinion the Marine Corps needs to take the lead in getting this project budgeted. FAA, DHS, Air Force, Navy, DOD and perhaps some other agencies should chip in.

This is not an optional program. We urgently need more renewable energy sources. The cost of failure to control global warming and allowing the sea level to rise is incalculable. It is already threatening Norfolk, VA. Projected sea level rise of one meter later in this century will make my home unlivable - and those of many other Pamlico County residents as well. One meter this century may well be an underestimate.

There is no single silver bullet. We need to explore every avenue.

Not just for the residents of Eastern North Carolina, but for the marines as well.

I plan to attend the meeting. I hope to hear from the Cherry Point representatives an informative discussion examining potential problems, including a technical explanation, along with proposed solutions. I want to see some empirical data backed by research. I would hope that an expert from NRL might appear. If the proposed solution is not to have wind farms in Pamlico County, I will be very disappointed.

One commissioner is quoted as saying "the Marine Corps deserve our respect just based on who they are." I share that commissioner's high regard for the marines. At the same time, I would hope that our marines are bending every effort to insure that we can share the land, sea and air space of Eastern North Carolina without precluding other future economic development in the region.

By the way, we should all recognize that effective alternate energy sources to replace the burning of fossil fuels is an urgent national security priority. In fact, the Department of the Navy (including the marines) has taken the lead in DOD in fostering alternate energy development.

I gather that the marines share a concern of a number of government agencies that wind farms present a particular challenge to radars, including air search and air control radars, including doppler radars for meteorology. The fundamental concern is radar clutter.

Clutter has been a major challenge for radar designers from the earliest days. Dealing with clutter has generated an alphabet soup of anti-clutter measures: STC, AGC, FTC, IAGC, MTI, frequency agility, circular polarization, Moving Target Detector, Pulse-Doppler Systems, and on and on. Clutter presents some of the same challenges as are presented by electronic and mechanical jamming.

Solving particular problems of clutter from wind farms may not be trivial, but is certainly surmountable.

The following is an executive summary of a 2008 report by The MITRE Corporation, one of our premier defense contractors with experience in this area.

Wind Farms And Radar

January 2008

The MITRE Corporation

1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

"Wind farms interfere with radar. This interference has led the FAA,

the DHS, and the DOD to contest many proposed wind turbines in the line

of sight of radar, stalling development of several thousands of MW of wind

energy. A large number of such denials is a serious impediment to the nation’s

mandated growth of sustainable energy.

"There is no fundamental physical constraint that prohibits the accu-

rate detection of aircraft and weather patterns around wind farms. On the

other hand, the nation’s aging long range radar infrastructure significantly

increases the challenge of distinguishing wind farm signatures from airplanes

or weather.

"Progress forward requires the development of mitigation measures, and

quantitative evaluation tools and metrics to determine when a wind farm

poses a sufficient threat to a radar installation for corrective action to be

taken. Mitigation measures may include modifications to wind farms (such

as methods to reduce radar cross section; and telemetry from wind farms to

radar), as well as modifications to radar (such as improvements in processing;

radar design modifications; radar replacement; and the use of gap fillers in

radar coverage).

"There is great potential for the mitigation procedures, though there

is currently no source of funding to test how proposed mitigations work in

practice. In general, the government and industry should cooperate to find

methods for funding studies of technical mitigations. NOAA has an excellent

research plan, but no adequate funding to carry it out.

"Once the potential for different mitigations are understood, we see no

scientific hurdle for constructing regulations that are technically based and

simple to understand and implement, with a single government entity tak-

ing responsibility for overseeing the process. In individual cases, the best

solution might be to replace the aging radar station with modern and flexi-

ble equipment that is more able to separate wind farm clutter from aircraft.

This is a win-win situation for national security, both improving our radar

infrastructure and promoting the growth of sustainable energy.

"Regulatory changes for air traffic could make considerable impact on

the problem. For example, the government could consider mandating that

the air space up to some reasonable altitude above an air-security radar

with potential turbine interference be a controlled space, with transponders

required for all aircraft flying in that space. This would both solve the

problem of radar interference over critical wind farms and would provide a

direct way to identify bad actors, flying without transponders.

"Current circumstances provide an interesting opportunity for improving

the aging radar infrastructure of the United States, by replacing radar that

inhibits the growth of wind farms with new, more flexible and more capable

systems, especially digital radar hardware and modern computing power.

Such improvements could significantly increase the security of U.S. airspace."

For what it's worth, in my opinion the Marine Corps needs to take the lead in getting this project budgeted. FAA, DHS, Air Force, Navy, DOD and perhaps some other agencies should chip in.

This is not an optional program. We urgently need more renewable energy sources. The cost of failure to control global warming and allowing the sea level to rise is incalculable. It is already threatening Norfolk, VA. Projected sea level rise of one meter later in this century will make my home unlivable - and those of many other Pamlico County residents as well. One meter this century may well be an underestimate.

There is no single silver bullet. We need to explore every avenue.

Not just for the residents of Eastern North Carolina, but for the marines as well.

Topic Tags:

environment,

government,

military,

national security

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: Eleanor Roosevelt's Diary

January 22, 1943, Eleanor Roosevelt travels from Washington to Christen the new USS Yorktown. She christened the first one in 1936 at Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock. As Mrs. Roosevelt explained, Yorktown (CV-5) gave a good account of herself in the war, but was lost at the battle of Midway. Now she was to christen the second one, USS Yorktown (CV-10), the second new large aircraft carrier of the Essex class, also built at Newport News. Here are Mrs. Roosevelt's thoughts on that occasion about the US shipbuilders.

The second Yorktown had a distinguished record in World War II, Korea, Viet Nam and in the Apollo program. She is still afloat, having been decommissioned in 1970 and in 1975 becoming a museum ship at Patriot's Point, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She is a National Historic Landmark.

The second Yorktown had a distinguished record in World War II, Korea, Viet Nam and in the Apollo program. She is still afloat, having been decommissioned in 1970 and in 1975 becoming a museum ship at Patriot's Point, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She is a National Historic Landmark.

Sunday, January 20, 2013

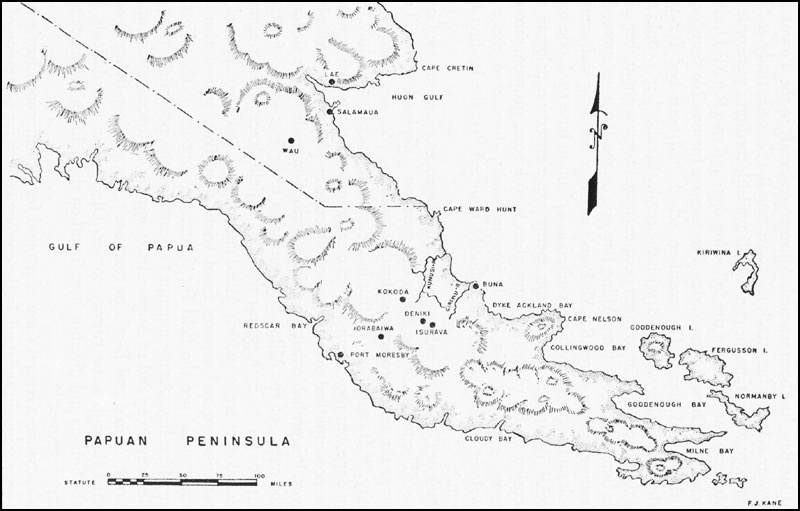

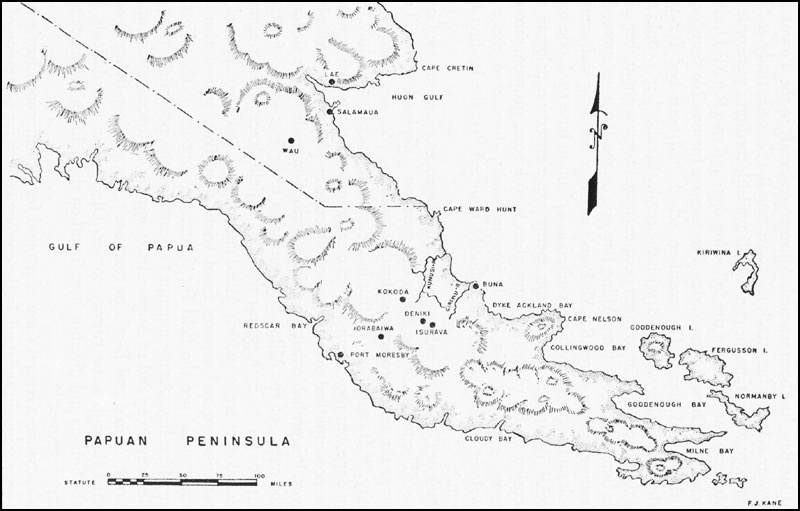

Seventy Years Ago: New Guinea

January 19, 1942, the Charlotte (NC) News reports news from New Guinea that MacArthur's forces have captured the Japanese stronghold of Sanananda on the north coast of Papua.

The report was only slightly premature. It was to take the Allied armies of the United States and Australia two more days to finally capture Sanananda, Buna and Gona. This effectively ended any imminent Japanese threat to Port Moresby, where the 27th Air Depot Group was hacking out a major aircraft repair facility from the jungle.

Casualties were more than twice as high as for American forces on Guadalcanal. One in eleven troops fighting in New Guinea died, compared to one in 37 on Guadalcanal.

The report was only slightly premature. It was to take the Allied armies of the United States and Australia two more days to finally capture Sanananda, Buna and Gona. This effectively ended any imminent Japanese threat to Port Moresby, where the 27th Air Depot Group was hacking out a major aircraft repair facility from the jungle.

Casualties were more than twice as high as for American forces on Guadalcanal. One in eleven troops fighting in New Guinea died, compared to one in 37 on Guadalcanal.

Monday, January 7, 2013

150 Years Ago: Yes, The Civil War Was About Slavery

Nearly sixty years ago, my American History professor lectured on all the other things besides slavery that might have contributed to the Civil War.

I was never persuaded that Americans went to war over protective tariffs.

I was persuaded, though, that northern Republicans fought for the Union, not to free the slaves, until perhaps after the Battle of Gettysburg.

No longer.

The New York Times' series "Disunion" has documented the centrality of slavery to the Civil War from the outset.

In a recent post in that series, Professor James Oakes of CUNY thoroughly lays that issue to rest. Not only did influential Republican voices clamor for the end of slavery, most of the incidents used to demonstrate Lincoln's purported reluctance to free slaves turn out to reflect quite the opposite - his determination to end slavery.

I was never persuaded that Americans went to war over protective tariffs.

I was persuaded, though, that northern Republicans fought for the Union, not to free the slaves, until perhaps after the Battle of Gettysburg.

No longer.

The New York Times' series "Disunion" has documented the centrality of slavery to the Civil War from the outset.

In a recent post in that series, Professor James Oakes of CUNY thoroughly lays that issue to rest. Not only did influential Republican voices clamor for the end of slavery, most of the incidents used to demonstrate Lincoln's purported reluctance to free slaves turn out to reflect quite the opposite - his determination to end slavery.

Topic Tags:

government,

history,

military

Saturday, January 5, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: VT Projectiles Shoot Down Japanese Dive Bomber

January 5, 1943. Task Group 67.2 (Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth) bombards a Japanese airfield and installations at Munda, New Georgia, Solomons Islands. After the rest of Task Force 67 joins TG 67.2, Japanese planes attack the force, just missing light cruiser Honolulu (CL 48) and damaging New Zealand light cruiser HMNZS Achilles, 18 miles south of Cape Hunter, Guadalcanal. In the action, light cruiser Helena (CL 50) becomes the first U.S. Navy ship to use 5 inch/38 caliber Mk. 32 proximity-fuzed projectiles in combat, downing a Japanese Aichi Type 99 carrier bomber (VAL) with her second salvo

This was a major technological triumph. These 5-inch projectiles contained a tiny radio proximity device, essentially a miniature radar, which caused the projectile to explode if it came close enough to the airplane to do damage. This system, under development since mid-1940, was a vast improvement over the mechanical time fuze previously used against aircraft. It also replaced contact fuzes that had to actually hit the aircraft to explode.

To conceal the purpose of the projectiles, they were designated as "VT-Fuzed projectiles" (Variable-Time fuze).

The story of development of the proximity fuze is detailed here in an article on the Naval Historical Center web site.

The greatest challenge was to ruggedize the miniature electronic tubes used in the circuitry back in the day before transistors.

Mark 53 Proximity Fuze

Monday, December 31, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: War In The Pacific

December 31, 1942. The Japanese military high command decides to evacuate forces from Guadalcanal. It will be a complex and challenging undertaking to withdraw forces, and will take more than a month. There will be more battles.

USS Essex, lead ship of a more powerful class of aircraft carriers, is commissioned today.

On New Guinea, after more than two months of jungle fighting against well-defended Japanese positions, the US Army I Corps was nearing victory at Buna on the north coast of New Guinea. Victory here will relieve pressure on Port Moresby.

USS Essex, lead ship of a more powerful class of aircraft carriers, is commissioned today.

On New Guinea, after more than two months of jungle fighting against well-defended Japanese positions, the US Army I Corps was nearing victory at Buna on the north coast of New Guinea. Victory here will relieve pressure on Port Moresby.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Women Auxiliary Territorial Service

On the home front in the US, women were tending their victory gardens, saving tin cans, riveting aircraft together and such like. In the U.K., it turns out some young women were drafted into various auxiliary services. This included manning antiaircraft artillery.

Some gave their lives. Here is one story.

Some gave their lives. Here is one story.

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: "I'll Be Home For Christmas"

My father left home in February, 1942. He had just returned to Tallahassee from the Carolina Maneuvers on December 5, 1941, two days before Pearl Harbor. By March he had been transferred to Mobile, Alabama to prepare for overseas movement. We didn't see him for over three years.

He missed three Christmases with his family. He was gone "for the duration" as we said it in those days. No one ever finished the phrase: duration of what?

A lot of fathers, brothers, sons, and even daughters missed a lot of Christmases in those years. We were all in it together.

"I'll be home for Christmas," one popular song put it. After dragging the story line out, the song closed "If only in my dreams."

Today we have soldiers who keep going back into combat. In 1942, it may have been a long time at the front, but usually only once. Today, the tours are shorter, but repeated.

We have had soldiers and marines in Afghanistan for twelve Christmases. Three times as long as World War II.

Don't forget our troops. It's time to bring them home.

He missed three Christmases with his family. He was gone "for the duration" as we said it in those days. No one ever finished the phrase: duration of what?

A lot of fathers, brothers, sons, and even daughters missed a lot of Christmases in those years. We were all in it together.

"I'll be home for Christmas," one popular song put it. After dragging the story line out, the song closed "If only in my dreams."

Today we have soldiers who keep going back into combat. In 1942, it may have been a long time at the front, but usually only once. Today, the tours are shorter, but repeated.

We have had soldiers and marines in Afghanistan for twelve Christmases. Three times as long as World War II.

Don't forget our troops. It's time to bring them home.

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Former Chief Justice Warren Burger: Second Amendment

Warren E. Burger, Chief Justice of the United States

(1969-86) had this to say in an article in Parade Magazine, January 14, 1990, page 4:

"The Constitution of the United States, in its Second Amendment, guarantees a "right of the people to keep and bear arms." However, the meaning of this clause cannot be understood except by looking to the purpose, the setting and the objectives of the draftsmen. The first 10 amendments -- the Bill of Rights -- were not drafted at Philadelphia in 1787; that document came two years later than the Constitution. Most of the states already had bills of rights, but the Constitution might not have been ratified in 1788 if the states had not had assurances that a national Bill of Rights would soon be added.

"People of that day were apprehensive about the new "monster" national government presented to them, and this helps explain the language and purpose of the Second Amendment. A few lines after the First Amendment's guarantees -- against "establishment of religion," "free exercise" of religion, free speech and free press -- came a guarantee that grew out of the deep-seated fear of a "national" or "standing" army. The same First Congress that approved the right to keep and bear arms also limited the national army to 840 men; Congress in the Second Amendment then provided:

"The Constitution of the United States, in its Second Amendment, guarantees a "right of the people to keep and bear arms." However, the meaning of this clause cannot be understood except by looking to the purpose, the setting and the objectives of the draftsmen. The first 10 amendments -- the Bill of Rights -- were not drafted at Philadelphia in 1787; that document came two years later than the Constitution. Most of the states already had bills of rights, but the Constitution might not have been ratified in 1788 if the states had not had assurances that a national Bill of Rights would soon be added.

"People of that day were apprehensive about the new "monster" national government presented to them, and this helps explain the language and purpose of the Second Amendment. A few lines after the First Amendment's guarantees -- against "establishment of religion," "free exercise" of religion, free speech and free press -- came a guarantee that grew out of the deep-seated fear of a "national" or "standing" army. The same First Congress that approved the right to keep and bear arms also limited the national army to 840 men; Congress in the Second Amendment then provided:

"A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.""In the 1789 debate in Congress on James Madison's proposed Bill of Rights, Elbridge Gerry argued that a state militia was necessary:

"to prevent the establishment of a standing army, the bane of liberty ... Whenever governments mean to invade the rights and liberties of the people, they always attempt to destroy the militia in order to raise an army upon their ruins."Plainly the goal of the Second Amendment was to prevent the establishment of a large standing army. That endeavor failed more than a century ago. We now maintain the second largest standing military force in the world. Only China's is larger.

Topic Tags:

government,

law,

military

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: General Patch Takes Command

December 9, 1942. Major General Alexander Patch, US Army, commander of the Americal Division, assumed command of all army and marine forces on Guadalcanal, replacing Marine General Vandegrift. Admiral Halsey remained in overall command of the South Pacific Area from his flagship at Noumea.

By February, 1943, Patch had expelled all Japanese from the island.

By February, 1943, Patch had expelled all Japanese from the island.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: First Year Of The Pacific War

The war had been going on for a year. It was mostly a naval war.

If the war were scored like a game of checkers, you would conclude that Japan was ahead. But Japan had made no significant advances since the early weeks. Repeated attempts to take control of Papua New Guinea had failed. Japan was hanging on to Buna, Salamaua and Lae on the northern coast by their fingernails.

Japanese soldiers on Guadalcanal had been unable to expel US Marines. The Japanese navy was unable to supply troops with food, much less with ammunition.

But fierce battles at sea had been costly to both sides. The score in ships sunk:

Warship losses in the First Year of the Pacific War.

If the war were scored like a game of checkers, you would conclude that Japan was ahead. But Japan had made no significant advances since the early weeks. Repeated attempts to take control of Papua New Guinea had failed. Japan was hanging on to Buna, Salamaua and Lae on the northern coast by their fingernails.

Japanese soldiers on Guadalcanal had been unable to expel US Marines. The Japanese navy was unable to supply troops with food, much less with ammunition.

But fierce battles at sea had been costly to both sides. The score in ships sunk:

Warship losses in the First Year of the Pacific War.

| U.S. | Allies | Japanese | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battleships | 2 | 2 RN | 2 |

| Fleet Carriers | 4 | - | 4 |

| Light Carriers | - | 1 RN | 2 |

| Heavy Cruisers | 5 | 3 RN , 1 Aus | 4 |

| Light Cruisers | 2 | 2 Dutch, 1 Aus | 2 |

| Destroyers | 23 | 8 Dutch, 7+3 RN. 2+2 Aus | 26 |

| Submarines | 7 | 5 Dutch | 21 |

Seventy Years Ago: 27th Air Depot Group Leaves Brisbane

Ten weeks after arriving in Australia, the 27th Air Depot Group has loaded up and shipped out from Brisbane. Destination: Port Moresby, New Guinea. The voyage will take six days.

The equipment they brought with them, designed to rebuild airplanes, was supplemented with all kinds of heavy equipment. Who would operate the equipment? The soldiers. My dad, M/Sgt J. Cox, was recruited to operate a bulldozer. He had operated road graders, bulldozers and other heavy equipment since he was a teenager. He would bulldoze landing strips, areas to pitch tents, build hangars, warehouses, aircraft taxiways, for example.

The soldiers had to build their own hangars, barracks, mess halls and other structures. But there was no lumber. Not to worry. There were plenty of logs in the jungle and the ships carried a complete sawmill. Among the aircraft mechanics, welders, electronic technicians and other specialists, there were soldiers who had operated sawmills.

Some of the 900-odd men were carried by truck for miles into a desolate area covered by fibrous waist-high Kunai grass laden with mosquitoes. Their camp was in a valley nicknemed "death valley" between two existing airfields.

It was mid-January before they began major construction. In the meantime the soldiers had only their barracks bags and field packs. Other supplies and equipment had to be brought from the ships and uncrated before field kitchens and tents could be set up. Forty percent of the soldiers spent their first weeks on site building the depot.

Among the wooden boxes were some marked "tools" and "aircraft parts;" "Attention M/Sgt Cox." When opened, they proved to contain sturdy cots, mosquito nets and air mattresses for greater comfort in the jungle.

In the Navy, we call it "forehandedness."

The equipment they brought with them, designed to rebuild airplanes, was supplemented with all kinds of heavy equipment. Who would operate the equipment? The soldiers. My dad, M/Sgt J. Cox, was recruited to operate a bulldozer. He had operated road graders, bulldozers and other heavy equipment since he was a teenager. He would bulldoze landing strips, areas to pitch tents, build hangars, warehouses, aircraft taxiways, for example.

The soldiers had to build their own hangars, barracks, mess halls and other structures. But there was no lumber. Not to worry. There were plenty of logs in the jungle and the ships carried a complete sawmill. Among the aircraft mechanics, welders, electronic technicians and other specialists, there were soldiers who had operated sawmills.

Some of the 900-odd men were carried by truck for miles into a desolate area covered by fibrous waist-high Kunai grass laden with mosquitoes. Their camp was in a valley nicknemed "death valley" between two existing airfields.

It was mid-January before they began major construction. In the meantime the soldiers had only their barracks bags and field packs. Other supplies and equipment had to be brought from the ships and uncrated before field kitchens and tents could be set up. Forty percent of the soldiers spent their first weeks on site building the depot.

Among the wooden boxes were some marked "tools" and "aircraft parts;" "Attention M/Sgt Cox." When opened, they proved to contain sturdy cots, mosquito nets and air mattresses for greater comfort in the jungle.

In the Navy, we call it "forehandedness."

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: 27th Air Depot Group In Australia

The 27th Air Depot Group had set up a temporary headquarters at Amberly Airfield, west of Ipswich not far from Brisbane. The Group refined their organization, conducted training and unloaded and sorted equipment in preparation for their planned move to New Guinea. They obtained heavy equipment to use for building their own warehouses, camps and hangars once they arrived in New Guinea. They were even to build their own airstrips.

But things were still unsettled in New Guinea.

During the early days days of September the Directorate of Air Transport had pressed every available plane, whether civil or military, into service to ferry an Australian regiment from Brisbane to Port Moresby. By 15 September, the exhausted troops facing the Japanese in the ridges above Port Moresby had been reinforced by three fresh Australian battalions; and on that same day the first American infantrymen to reach New Guinea, Company E, 126th Infantry of the 32d Division, landed by transport plane at Seven-Mile Airdrome. This had been a test flight to determine the feasibility of moving units by air transport, and by 24 September the 128th Infantry Regiment, less artillery, had been flown to Port Moresby, where the remainder of the 126th Infantry came in by water on 28 September. On that day the reinforced Australians launched an attack which broke the enemy's defenses on Iorabaiwa Ridge and then in the face of tenacious resistance forced their way back toward Kokoda. Though it would take over a month to reach that place, with its useful airfield, the turning point in the Japanese attempt to take Port Moresby from the rear had come. Bitter fighting lay ahead, but the battle soon would be for Buna instead of for Moresby.

It had been necessary for army air force leaders to divide their attention between operations and reorganization. General Kenney had been preceded to Australia by Brig. Gens. Ennis C. Whitehead, an experienced fighter commander, and Kenneth N. Walker, expert in bombardment aviation; Brig. Gen. Donald Wilson, whom Kenney proposed to use as chief of staff, soon followed. Plans, on which General Kenney had been briefed in Washington, called for organization of American units into a distinct air force that would be largely free of obligations for the immediate defense of Australia in order to concentrate on support of a rapidly moving offensive to the north. On 7 August, three days after Kenney assumed command in Australia, MacArthur requested authorization for an American air force and suggested the designation of Fifth Air Force in honor of his fighter and bomber commands in the Philippines. This request was promptly granted, and the Fifth Air Force was officially constituted on 3 September. Kenney immediately assumed command, retaining in addition his command of the Allied Air Forces.

Problems of maintenance loomed large. In August Kenney described maintenance on his B-17's: "We are salvaging even the skin for large patchwork from twenty millimetre explosive fire; to patch up smaller holes we are flattening out tin cans and using them. Every good rib and bulkhead of a wrecked airplane is religiously saved to replace shot up members of other airplanes. Lack of bearings for Allison engines grounded many fighters; requisitioned in August, the bearings were not available for shipment until October, by which time main bearings in five out of six engines needed changing. Improper tools for Pratt & Whitney engines delayed repair of grounded B-26's and transports. Most discouraging of all was the difficulty getting the P-38's ready for combat. By October approximately sixty of these fighters had reached the theater, but none had seen combat. First, the fuel tanks began to leak, requiring repair or replacement, and then superchargers, water coolers, inverters, and armament all required major adjustment or repair. As a consequence, it was not until late in December that P-38's flew a major combat mission over New Guinea.

While preparing for the eventual move to New Guinea, the 27th Air Depot Group, trained and organized to rebuild aircraft, joined in the effort to keep the aircraft flying.

But things were still unsettled in New Guinea.

During the early days days of September the Directorate of Air Transport had pressed every available plane, whether civil or military, into service to ferry an Australian regiment from Brisbane to Port Moresby. By 15 September, the exhausted troops facing the Japanese in the ridges above Port Moresby had been reinforced by three fresh Australian battalions; and on that same day the first American infantrymen to reach New Guinea, Company E, 126th Infantry of the 32d Division, landed by transport plane at Seven-Mile Airdrome. This had been a test flight to determine the feasibility of moving units by air transport, and by 24 September the 128th Infantry Regiment, less artillery, had been flown to Port Moresby, where the remainder of the 126th Infantry came in by water on 28 September. On that day the reinforced Australians launched an attack which broke the enemy's defenses on Iorabaiwa Ridge and then in the face of tenacious resistance forced their way back toward Kokoda. Though it would take over a month to reach that place, with its useful airfield, the turning point in the Japanese attempt to take Port Moresby from the rear had come. Bitter fighting lay ahead, but the battle soon would be for Buna instead of for Moresby.

It had been necessary for army air force leaders to divide their attention between operations and reorganization. General Kenney had been preceded to Australia by Brig. Gens. Ennis C. Whitehead, an experienced fighter commander, and Kenneth N. Walker, expert in bombardment aviation; Brig. Gen. Donald Wilson, whom Kenney proposed to use as chief of staff, soon followed. Plans, on which General Kenney had been briefed in Washington, called for organization of American units into a distinct air force that would be largely free of obligations for the immediate defense of Australia in order to concentrate on support of a rapidly moving offensive to the north. On 7 August, three days after Kenney assumed command in Australia, MacArthur requested authorization for an American air force and suggested the designation of Fifth Air Force in honor of his fighter and bomber commands in the Philippines. This request was promptly granted, and the Fifth Air Force was officially constituted on 3 September. Kenney immediately assumed command, retaining in addition his command of the Allied Air Forces.

Problems of maintenance loomed large. In August Kenney described maintenance on his B-17's: "We are salvaging even the skin for large patchwork from twenty millimetre explosive fire; to patch up smaller holes we are flattening out tin cans and using them. Every good rib and bulkhead of a wrecked airplane is religiously saved to replace shot up members of other airplanes. Lack of bearings for Allison engines grounded many fighters; requisitioned in August, the bearings were not available for shipment until October, by which time main bearings in five out of six engines needed changing. Improper tools for Pratt & Whitney engines delayed repair of grounded B-26's and transports. Most discouraging of all was the difficulty getting the P-38's ready for combat. By October approximately sixty of these fighters had reached the theater, but none had seen combat. First, the fuel tanks began to leak, requiring repair or replacement, and then superchargers, water coolers, inverters, and armament all required major adjustment or repair. As a consequence, it was not until late in December that P-38's flew a major combat mission over New Guinea.

While preparing for the eventual move to New Guinea, the 27th Air Depot Group, trained and organized to rebuild aircraft, joined in the effort to keep the aircraft flying.

Friday, November 30, 2012

Sixty-Eight Years Ago: Buried Spitfires

In August, 1945, Royal Air Force troops in Burma had received perhaps as many as 140 brand new Spitfires in shipping crates. No longer needed for the war effort, and with faster aircraft coming off the production lines, what to do with them?

Apparently it was decided to bury them in their shipping crates.

Nearly seventy years later, following British abandonment of Burma as a colony and decades of political turmoil, improving relations have led to discovery of some of those aircraft after a sixteen-year search by a British farmer and aviation enthusiast.

There are various versions of the story and a number of curious aspects. For example, apparently the burying was done by the US Army. The project was helped along by the intervention of the British Prime Minister with Myanmar officials.

It is expected that excavation will begin after the first of the year. Only then will the presence of the aircraft be confirmed. The first site excavated will be near the runway at the Yangon (formerly known as Rangoon) international airport. There may be other burial sites as well.

Stand by for further news.

Apparently it was decided to bury them in their shipping crates.

Nearly seventy years later, following British abandonment of Burma as a colony and decades of political turmoil, improving relations have led to discovery of some of those aircraft after a sixteen-year search by a British farmer and aviation enthusiast.

There are various versions of the story and a number of curious aspects. For example, apparently the burying was done by the US Army. The project was helped along by the intervention of the British Prime Minister with Myanmar officials.

It is expected that excavation will begin after the first of the year. Only then will the presence of the aircraft be confirmed. The first site excavated will be near the runway at the Yangon (formerly known as Rangoon) international airport. There may be other burial sites as well.

Stand by for further news.

Thursday, November 29, 2012

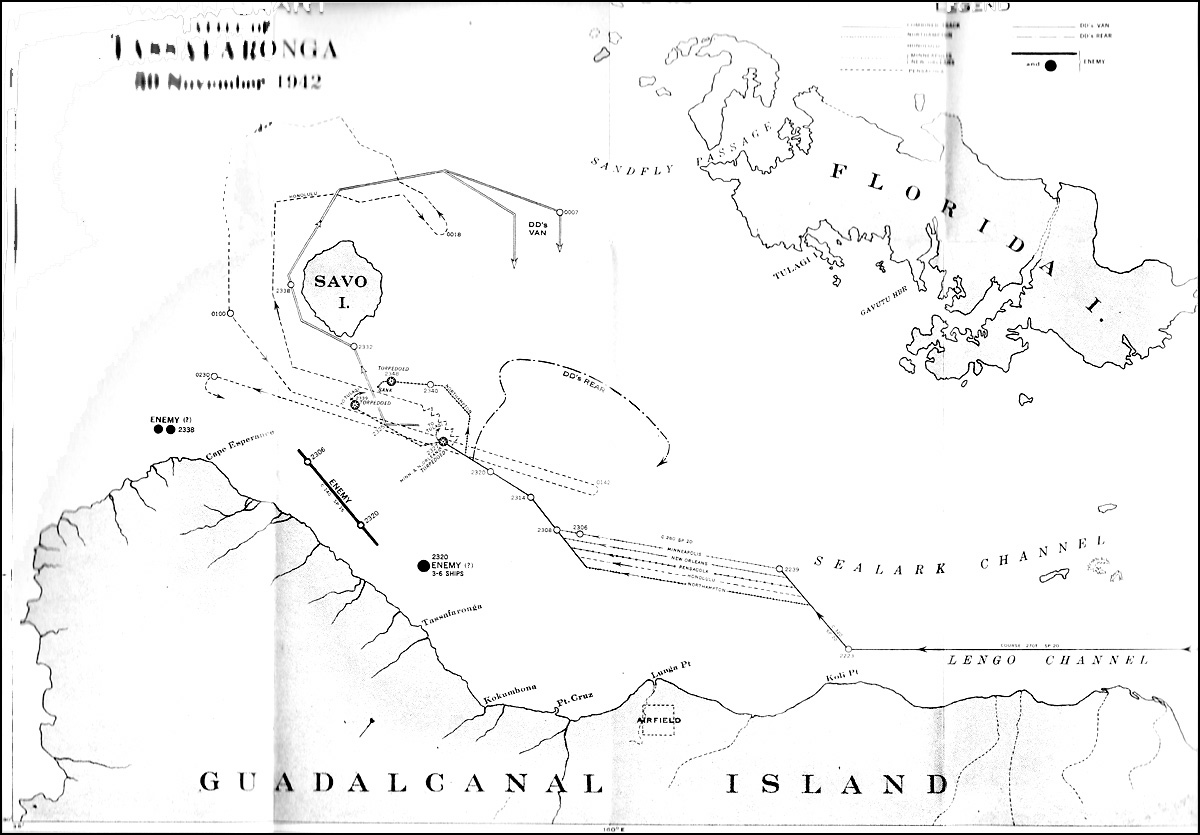

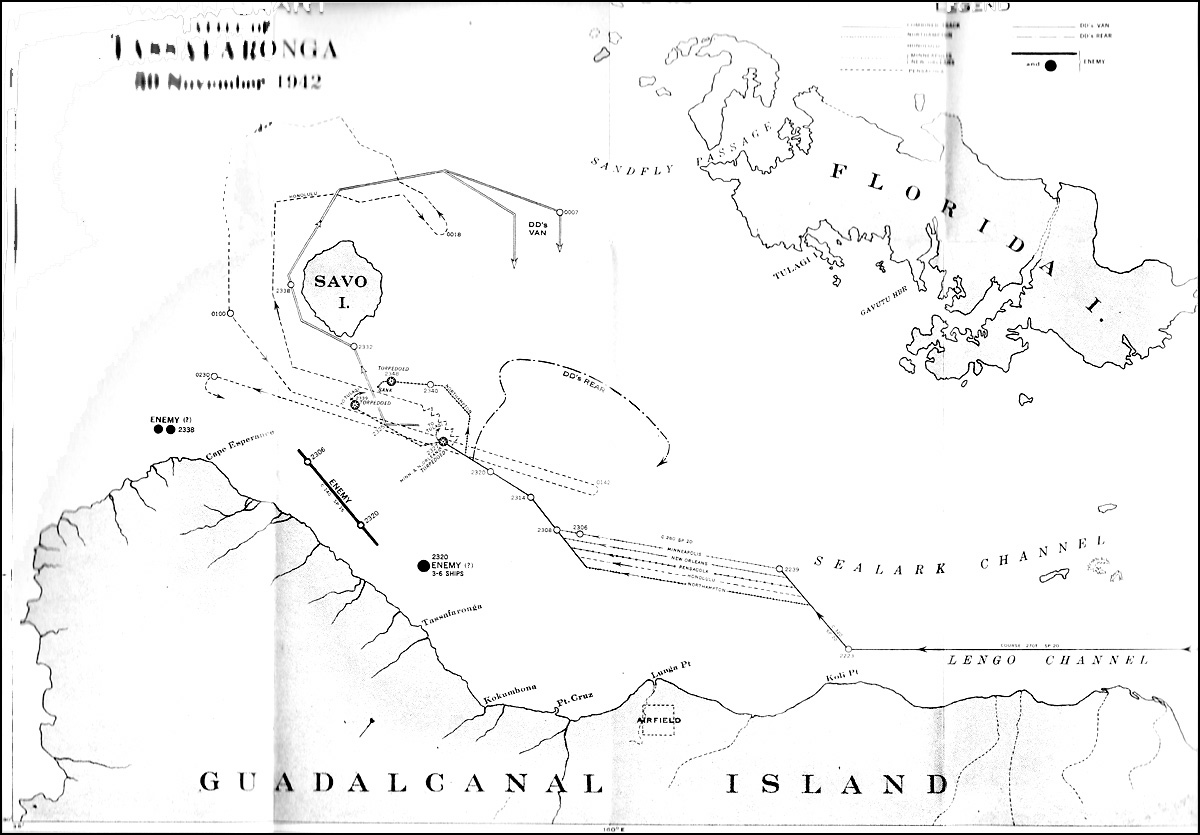

Seventy Years Ago: Battle Of Tassafaronga

Japanese Army forces on Guadalcanal were desperately short of food and on November 26, 1942, radioed pleading for more. The previous three weeks, only submarines had been able to deliver supplies. Each submarine delivered about a days' supply, but the difficulty of offloading and delivering the food through the jungle reduced what reached the troops. The troops were living on one-third rations.

Japan had resorted to submarines because they were unable to rely on surface ships. A combination of US aircraft operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, US PT Boats operating from Tulagi and US surface warships had prevented Japanese resupply operations by ship.

The Japanese developed a new plan. Resupply by high speed destroyers carrying floating drums of food and medical supplies. The drums, connected to each other by line, were to be carried on the decks of six destroyers, escorted by two more. The destroyers would approach at high speed, drop the drums overboard and return to base. Soldiers would swim out and recover the drums.

Following the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Admiral Halsey, Commander of the Southern Pacific Command, reorganized his surface warfare forces, forming a new Task Force, TF 67, at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, about 580 miles from Guadalcanal. The Task Force, initially under RADM Kinkaid, was reassigned to RADM Carleton H. Wright on November 28.

TF 67's job: intercept and destroy any Japanese surface force coming to the aid of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

The U.S. victory at the Battle of Guadalcanal had cost Halsey 18 ships sunk or so badly damaged that extensive repairs were required. With the exception of destroyers, Halsey's only available surface units were the carrier Enterprise, the battleship Washington, and the light cruiser San Diego at Noumea and the heavy cruisers Northampton and Pensacola at Espiritu Santo.

Several other ships were en route to the South Pacific. By 25 November, as intelligence was piecing together a clearer picture of Japanese plans, Halsey had assembled a force adequate to counter the expected offensive. At Nandi in the Fijis lay the carrier Saratoga, the battleships North Carolina, Colorado, and Maryland, and the light cruiser San Juan. The heavy cruisers New Orleans, Northampton, and Pensacola, and the light cruiser Honolulu were stationed at Espiritu Santo. These last two, together with the heavy cruiser Minneapolis which arrived on the 27th, had come from Pearl Harbor. Here also on the 27th were the destroyers Drayton (which had accompanied the Minneapolis), Fletcher Maury, and Perkins.

On 27 November, these 5 cruisers and 4 destroyers at Espiritu Santo were grouped in to a separate task force, Task Force William, under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, with general instructions from Halsey to intercept any Japanese surface forces approaching Guadalcanal. Admiral Kinkaid prepared a detailed set of operational orders for the Force, but, before he could go over them with his captains, he was ordered to other duty. He was replaced by Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, who had just made port in the Minneapolis.

Task Force William consisted of four heavy cruisers: Minneapolis, New Orleans, Northampton and Pensacola. Admiral Wright was embarked in Minneapolis;

One light cruiser: Honolulu, with RADM Tisdale embarked; Four destroyers: Drayton, Fletcher, Maury, Perkins. USS Fletcher was the fleet's newest and most powerful destroyer. Her CO, Commander William M. Cole, was in charge of the destroyer unit.

On 29 November the Task Force was moored at Espiritu Santo on 12 hours notice for getting underway. Admiral Wright held a conference, attended by Admiral Tisdale and the commanding officers of the 9 ships, at which the operation plan drawn up by Admiral Kinkaid was "briefly discussed."

At 1940 Admiral Wright received orders to prepare to depart with his force at the earliest possible moment, and to proceed at the best possible speed to intercept an enemy group of 6 destroyers and 6 transports which was expected to arrive off Guadalcanal the next night. He directed Task Force WILLIAM to make all preparations necessary to get under way immediately, and advised COMSOPAC that his ships would be ready to sortie at midnight.

Three hours later COMSOPAC ordered Admiral Wright to proceed with all available units, pass through Lengo Channel (between Guadalcanal and Florida Islands), and intercept the Japanese off Tassafaronga on the northwestern shore of Guadalcanal. Later, Admiral Wright received information that enemy combatant ships might be substituted for the transports, or that the Japanese force might consist wholly of destroyers, and that a hostile landing might be attempted off Tassafaronga earlier than 2300, 30 November. He received no further advices respecting the size or composition of the opposing units.

Admiral Wright promptly put into effect, with minor modifications, Admiral Kinkaid's operation plan, and set midnight as the zero hour for his ships to sortie. Actually the destroyers got under way at 2310, the cruisers at 2335. The whole Force cleared the well-mined, unlighted harbor of Espiritu Santo without incident and shaped its course to pass northeast of San Cristobal Island.

Task Force WILLIAM cleared Lengo Channel at 2225 at a speed of 20 knots. Its average speed made good from midnight, 29 November, when it left Espiritu Santo until it entered Lengo Channel at 2140, 30 November, was 28.2 knots. The cruisers steamed in column, 1,000 yards apart, while the destroyers in the van bore 300° T., 4,000 yards from the Minneapolis. The night was very dark, the sky completely overcast. Maximum surface visibility was not over 2 miles.

Admiral Wright had prepositioned sea planes from the cruisers at Tulagi. Their instructions were to take off in time to patrol the area between Cape Esperance and Lunga Point starting at 2200. They carried flares to drop at Admiral Wright's command. The rest of Admiral Wright's plan depended on using the Navy's new SG surface search radar to gain the advantage of surprise. The four destroyers were in the van (ahead), followed by the cruisers steaming in column 1,000 yards apart. Two additional destroyers, Lamson and Lardner, joined the force at 2100, bringing up the rear. Lamson's CO, Commander Abercrombie, was senior to Cole, but had no copies of the plan, no surface radar, and no knowledge of what was going on. He was therefore unable to assume command of the destroyer force.

At 2306, Minneapolis' SG radar picks up two objects off Cape Esperance. At 2316, Cdr Cole, in accordance with the plan, requested permission to launch torpedo attack on enemy formation of 5 ships, distant 7,000 yards.

About 2321, Admiral Wright ordered ships to commence firing star shells (for illumination) and explosive shells. Apparently TF 67 had caught the Japanese by surprise. The force engaged eight Japanese destroyers or cruisers using fire control radar for aiming. After a few minutes, four of the radar targets disappeared from the radar and some were visually seen to explode and sink.

There was some confusion in attempts to correlate ranges and bearings of Japanese ships, but as of 2326, it appeared that TF67 had won a great victory.

At 2327 a Japanese torpedo struck Minneapolis', blowing off her bow. The ship kept firing until her engineering plant failed and lost power. At 2328, New Orleans was torpedoed, losing her bow as far aft as Turret II. At 2329, a torpedo struck Pensacola on the port side aft, the ship erupted in flames, and fire raged for hours. At 2348, Northampton was torpedoed. Despite valiant efforts to save her, she finally sank about 0300.

Thus, within a few minutes, what had seemed a great victory turned into a resounding loss. One US heavy cruiser sunk, three out of action for months, 395 sailors killed.

As it turned out, only one Japanese destroyer was lost and 197 killed.

Even so, TF67 succeeded in preventing Japanese resupply of their troops on Guadalcanal.

The battle revealed continuing shortcomings in the use of radar.

The surface force was not yet aware that reliability problems affecting submarine torpedoes also applied to those launched by surface ships. Corrective action was many months away.

But damage control and firefighting crews performed magnificently. It is almost inconceivable that Minneapolis, New Orleans and Pensacola were saved and lived to fight another day.

The US Navy still did not know how powerful and effective Japanese type 93 surface-launched torpedoes were. Admiral Wright, in his after action report, still thought the sips had been torpedoed by undetected submarines. There were, after all, no Japanese surface ships within what we believed to be torpedo range.

We would not learn of their technological superiority until later in 1943, when intact torpedoes were captured.

Japan had resorted to submarines because they were unable to rely on surface ships. A combination of US aircraft operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, US PT Boats operating from Tulagi and US surface warships had prevented Japanese resupply operations by ship.

The Japanese developed a new plan. Resupply by high speed destroyers carrying floating drums of food and medical supplies. The drums, connected to each other by line, were to be carried on the decks of six destroyers, escorted by two more. The destroyers would approach at high speed, drop the drums overboard and return to base. Soldiers would swim out and recover the drums.

Following the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Admiral Halsey, Commander of the Southern Pacific Command, reorganized his surface warfare forces, forming a new Task Force, TF 67, at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, about 580 miles from Guadalcanal. The Task Force, initially under RADM Kinkaid, was reassigned to RADM Carleton H. Wright on November 28.

TF 67's job: intercept and destroy any Japanese surface force coming to the aid of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

The U.S. victory at the Battle of Guadalcanal had cost Halsey 18 ships sunk or so badly damaged that extensive repairs were required. With the exception of destroyers, Halsey's only available surface units were the carrier Enterprise, the battleship Washington, and the light cruiser San Diego at Noumea and the heavy cruisers Northampton and Pensacola at Espiritu Santo.

Several other ships were en route to the South Pacific. By 25 November, as intelligence was piecing together a clearer picture of Japanese plans, Halsey had assembled a force adequate to counter the expected offensive. At Nandi in the Fijis lay the carrier Saratoga, the battleships North Carolina, Colorado, and Maryland, and the light cruiser San Juan. The heavy cruisers New Orleans, Northampton, and Pensacola, and the light cruiser Honolulu were stationed at Espiritu Santo. These last two, together with the heavy cruiser Minneapolis which arrived on the 27th, had come from Pearl Harbor. Here also on the 27th were the destroyers Drayton (which had accompanied the Minneapolis), Fletcher Maury, and Perkins.

On 27 November, these 5 cruisers and 4 destroyers at Espiritu Santo were grouped in to a separate task force, Task Force William, under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, with general instructions from Halsey to intercept any Japanese surface forces approaching Guadalcanal. Admiral Kinkaid prepared a detailed set of operational orders for the Force, but, before he could go over them with his captains, he was ordered to other duty. He was replaced by Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, who had just made port in the Minneapolis.

Task Force William consisted of four heavy cruisers: Minneapolis, New Orleans, Northampton and Pensacola. Admiral Wright was embarked in Minneapolis;

One light cruiser: Honolulu, with RADM Tisdale embarked; Four destroyers: Drayton, Fletcher, Maury, Perkins. USS Fletcher was the fleet's newest and most powerful destroyer. Her CO, Commander William M. Cole, was in charge of the destroyer unit.

On 29 November the Task Force was moored at Espiritu Santo on 12 hours notice for getting underway. Admiral Wright held a conference, attended by Admiral Tisdale and the commanding officers of the 9 ships, at which the operation plan drawn up by Admiral Kinkaid was "briefly discussed."

At 1940 Admiral Wright received orders to prepare to depart with his force at the earliest possible moment, and to proceed at the best possible speed to intercept an enemy group of 6 destroyers and 6 transports which was expected to arrive off Guadalcanal the next night. He directed Task Force WILLIAM to make all preparations necessary to get under way immediately, and advised COMSOPAC that his ships would be ready to sortie at midnight.

Three hours later COMSOPAC ordered Admiral Wright to proceed with all available units, pass through Lengo Channel (between Guadalcanal and Florida Islands), and intercept the Japanese off Tassafaronga on the northwestern shore of Guadalcanal. Later, Admiral Wright received information that enemy combatant ships might be substituted for the transports, or that the Japanese force might consist wholly of destroyers, and that a hostile landing might be attempted off Tassafaronga earlier than 2300, 30 November. He received no further advices respecting the size or composition of the opposing units.

Admiral Wright promptly put into effect, with minor modifications, Admiral Kinkaid's operation plan, and set midnight as the zero hour for his ships to sortie. Actually the destroyers got under way at 2310, the cruisers at 2335. The whole Force cleared the well-mined, unlighted harbor of Espiritu Santo without incident and shaped its course to pass northeast of San Cristobal Island.

Task Force WILLIAM cleared Lengo Channel at 2225 at a speed of 20 knots. Its average speed made good from midnight, 29 November, when it left Espiritu Santo until it entered Lengo Channel at 2140, 30 November, was 28.2 knots. The cruisers steamed in column, 1,000 yards apart, while the destroyers in the van bore 300° T., 4,000 yards from the Minneapolis. The night was very dark, the sky completely overcast. Maximum surface visibility was not over 2 miles.

Admiral Wright had prepositioned sea planes from the cruisers at Tulagi. Their instructions were to take off in time to patrol the area between Cape Esperance and Lunga Point starting at 2200. They carried flares to drop at Admiral Wright's command. The rest of Admiral Wright's plan depended on using the Navy's new SG surface search radar to gain the advantage of surprise. The four destroyers were in the van (ahead), followed by the cruisers steaming in column 1,000 yards apart. Two additional destroyers, Lamson and Lardner, joined the force at 2100, bringing up the rear. Lamson's CO, Commander Abercrombie, was senior to Cole, but had no copies of the plan, no surface radar, and no knowledge of what was going on. He was therefore unable to assume command of the destroyer force.

At 2306, Minneapolis' SG radar picks up two objects off Cape Esperance. At 2316, Cdr Cole, in accordance with the plan, requested permission to launch torpedo attack on enemy formation of 5 ships, distant 7,000 yards.

About 2321, Admiral Wright ordered ships to commence firing star shells (for illumination) and explosive shells. Apparently TF 67 had caught the Japanese by surprise. The force engaged eight Japanese destroyers or cruisers using fire control radar for aiming. After a few minutes, four of the radar targets disappeared from the radar and some were visually seen to explode and sink.

There was some confusion in attempts to correlate ranges and bearings of Japanese ships, but as of 2326, it appeared that TF67 had won a great victory.

At 2327 a Japanese torpedo struck Minneapolis', blowing off her bow. The ship kept firing until her engineering plant failed and lost power. At 2328, New Orleans was torpedoed, losing her bow as far aft as Turret II. At 2329, a torpedo struck Pensacola on the port side aft, the ship erupted in flames, and fire raged for hours. At 2348, Northampton was torpedoed. Despite valiant efforts to save her, she finally sank about 0300.

Thus, within a few minutes, what had seemed a great victory turned into a resounding loss. One US heavy cruiser sunk, three out of action for months, 395 sailors killed.

As it turned out, only one Japanese destroyer was lost and 197 killed.

Even so, TF67 succeeded in preventing Japanese resupply of their troops on Guadalcanal.

The battle revealed continuing shortcomings in the use of radar.

The surface force was not yet aware that reliability problems affecting submarine torpedoes also applied to those launched by surface ships. Corrective action was many months away.

But damage control and firefighting crews performed magnificently. It is almost inconceivable that Minneapolis, New Orleans and Pensacola were saved and lived to fight another day.

New Orleans at Tulagi

Minneapolis at Tulagi

The US Navy still did not know how powerful and effective Japanese type 93 surface-launched torpedoes were. Admiral Wright, in his after action report, still thought the sips had been torpedoed by undetected submarines. There were, after all, no Japanese surface ships within what we believed to be torpedo range.

We would not learn of their technological superiority until later in 1943, when intact torpedoes were captured.

Thursday, November 15, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Naval Battle Of Guadalcanal, Phase II

The first phase, November 12-13 of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal had resulted in the deaths of US Admirals Scott and Callaghan and the loss of two light cruisers and four destroyers. Japan lost battleship Hiei, two destroyers and seven transports.

Admiral Abe withdrew his forces, including his remaining battleship, Kirishima one light cruiser and eleven destroyers. Yamamoto postponed the planned Japanese landing on Guadalcanal until November 15.

The US had paid a high price for a two-day delay. Callaghan's forces thought they had won a great victory. Subsequent analysis revealed that Callaghan's force disposition failed to make best use of the capabilities of radar, with which he was unfamiliar, and that he had issued unclear and confusing orders.

The truth is, that once again Japanese training in night combat operations and superior Japanese torpedoes had inflicted a tactical defeat on American forces.

Strategically, Callaghan and Scott had turned back the Japanese invasion force.

Japan remained committed to reinforcing their troops on Guadalcanal and pushing the Americans off the island. They started the force back toward Guadalcanal, with battleship Kirishima, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and nine destroyers under command of Rear Admiral Kondo.

Halsey had few undamaged forces to send in to the fray. He dare not send the damaged Enterprise into a night time engagement. But he decided to send most of Enterprise's escorts, including four destroyers and the fleet's newest battleships, USS South Dakota (BB-57) and USS Washington (BB-58) under command of Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, embarked in Washington.

Admiral Lee understood radar. He also understood tactics. He spent much of the evening of November 14 discussing how to use the ship's radar with Washington's commanding officer and gunnery officer. They knew what to do.

About 2300 that evening, Washington and South Dakota radars detected the Japanese forces, now under command of Admiral Kondo, in the vicinity of Savo Island. All ships were at general quarters (battle stations) and expecting action.

A few minutes after spotting the Japanese force, both Washington and South Dakota opened fire. The four US destroyers engaged the Japanese cruisers. Within minutes, two were sunk by Japanese torpedoes, a third had lost her bow, and the fourth took a hit in the engine room, taking her out of the action.

That left two new, untried battleships in defense of Guadalcanal.

The Japanese spotted South Dakota and brought all their guns to bear. Between midnight and 0030, the battleship was hit by 26 Japanese projectiles, none of which penetrated her armor. But about that time, South Dakota suffered a series of electrical failures, rendering her blind (no radar), dumb (no radio communications) and somewhat lame, though she suffered no major structural damage. She steered away from the action, in the direction of a previously agreed rendezvous point.

The electrical failures may have been caused by failure of automatic bus transfer switches (ABT) to work properly. Similar failures may have contributed to loss of Yorktown at Midway.

In any event, this left USS Washington alone against a Japanese battleship, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and as many as nine destroyers still effective. The Japanese were still concentrating their fire on South Dakota and failed to spot Washington as she approached the action.

Once Admiral Lee was certain who was friend and foe, Washington opened fire on Kirishima at a range of about 9,000 yards. Kirishima and the destroyer Ayanami were badly damaged and burning. Both ships were scuttled and abandoned about 0325.

Believing the way clear for the invasion force, Kondo withdrew his remaining ships

The four Japanese transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal by 04:00 on 15 November, and the escort destroyers raced back up the Slot toward safer waters. Aircraft from Henderson field attacked the transports beginning about 0600, joined by field artillery from ground forces. Only 2,000–3,000 of the Japanese troops originally embarked actually made it to Guadalcanal, and most of their ammunition and food supplies were lost.

This was the last major attempt by Japan to establish control of the seas around Guadalcanal and to retake the island, though there would be more skirmishes.

Admiral Abe withdrew his forces, including his remaining battleship, Kirishima one light cruiser and eleven destroyers. Yamamoto postponed the planned Japanese landing on Guadalcanal until November 15.

The US had paid a high price for a two-day delay. Callaghan's forces thought they had won a great victory. Subsequent analysis revealed that Callaghan's force disposition failed to make best use of the capabilities of radar, with which he was unfamiliar, and that he had issued unclear and confusing orders.

The truth is, that once again Japanese training in night combat operations and superior Japanese torpedoes had inflicted a tactical defeat on American forces.

Strategically, Callaghan and Scott had turned back the Japanese invasion force.

Japan remained committed to reinforcing their troops on Guadalcanal and pushing the Americans off the island. They started the force back toward Guadalcanal, with battleship Kirishima, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and nine destroyers under command of Rear Admiral Kondo.

Halsey had few undamaged forces to send in to the fray. He dare not send the damaged Enterprise into a night time engagement. But he decided to send most of Enterprise's escorts, including four destroyers and the fleet's newest battleships, USS South Dakota (BB-57) and USS Washington (BB-58) under command of Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, embarked in Washington.

Admiral Lee understood radar. He also understood tactics. He spent much of the evening of November 14 discussing how to use the ship's radar with Washington's commanding officer and gunnery officer. They knew what to do.

About 2300 that evening, Washington and South Dakota radars detected the Japanese forces, now under command of Admiral Kondo, in the vicinity of Savo Island. All ships were at general quarters (battle stations) and expecting action.

A few minutes after spotting the Japanese force, both Washington and South Dakota opened fire. The four US destroyers engaged the Japanese cruisers. Within minutes, two were sunk by Japanese torpedoes, a third had lost her bow, and the fourth took a hit in the engine room, taking her out of the action.

That left two new, untried battleships in defense of Guadalcanal.

The Japanese spotted South Dakota and brought all their guns to bear. Between midnight and 0030, the battleship was hit by 26 Japanese projectiles, none of which penetrated her armor. But about that time, South Dakota suffered a series of electrical failures, rendering her blind (no radar), dumb (no radio communications) and somewhat lame, though she suffered no major structural damage. She steered away from the action, in the direction of a previously agreed rendezvous point.

The electrical failures may have been caused by failure of automatic bus transfer switches (ABT) to work properly. Similar failures may have contributed to loss of Yorktown at Midway.

In any event, this left USS Washington alone against a Japanese battleship, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and as many as nine destroyers still effective. The Japanese were still concentrating their fire on South Dakota and failed to spot Washington as she approached the action.

Once Admiral Lee was certain who was friend and foe, Washington opened fire on Kirishima at a range of about 9,000 yards. Kirishima and the destroyer Ayanami were badly damaged and burning. Both ships were scuttled and abandoned about 0325.

Believing the way clear for the invasion force, Kondo withdrew his remaining ships

The four Japanese transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal by 04:00 on 15 November, and the escort destroyers raced back up the Slot toward safer waters. Aircraft from Henderson field attacked the transports beginning about 0600, joined by field artillery from ground forces. Only 2,000–3,000 of the Japanese troops originally embarked actually made it to Guadalcanal, and most of their ammunition and food supplies were lost.

This was the last major attempt by Japan to establish control of the seas around Guadalcanal and to retake the island, though there would be more skirmishes.

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Naval Battle Of Guadalcanal

For almost three months, Japanese forces had tried mightily to dislodge the Marines from Guadalcanal, without success. Every Japanese effort to reinforce their army forces on the island had been thwarted or at least limited by the US Navy.

Japan had achieved major successes against the US Navy, including submarine attacks on USS Saratoga and battleship North Carolina, under repair at Pearl Harbor. In late October, Japan sank the carrier USS Hornet and thought they might have sunk Enterprise. Now they planned to send a powerful surface force to bombard Henderson Field, where the "Cactus Air Force" of Marine, Navy and Army aircraft continued to operate with deadly effect against Japanese naval forces trying to reinforce Guadalcanal.

The night of November 12/13, 1942, the Japanese bombardment force under Admiral Abe approached the area, passing south of Savo Island, with two battleships, a light cruiser and thirteen escorting destroyers. The battleships were armed with high explosive projectiles to do maximum damage against the aircraft and fuel dumps at Henderson Field. Such projectiles would be of limited use against battleships and heavy cruisers, but Abe expected no opposition.

The Enterprise had not been sunk. She was undergoing urgent repair at the harbor of Noumea. Her formation was still a powerful force: the fast battleships Washington and South Dakota, the heavy cruiser Northampton, the light cruiser San Diego and six destroyers were protecting her.

At Espiritou Santo, moreover, Halsey retained Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner's transport units, to conduct another supply run to be completed by 12 November. In his force were seven transports carrying the 1st Marine Aviation Engineer Regiment, the U.S. Army's 182nd Infantry (National Guard) Regiment and supplies to sustain the forces on the island. Turner had a very potent escort: heavy cruisers Portland and San Francisco, light cruisers Helena, Atlanta and Juneau, plus nine destroyers. Turner move his forces in two separate moves, first the Engineers on three transports, with Atlanta and three destroyers as escorts, under command of Rear-Admiral Norman C. Scott, victor at Cape Esperance. Turner himself would take the rest of the forces, with his escorts under command of Rear-Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, former Chief-of-Staff to Admiral Ghormley.

Halsey had an advantage: advance knowledge from COMINT of Japanese plans. He realized that every US gain to that point was at stake. But he could only get a third of his forces underway in time. Enterprise and her screen, augmented by heavy cruiser Pensacola, departed Nouméa; but they would not arrive in time to stop the Japanese. Admiral Turner's transports reached Guadalcanal in the early hours of 12 November, and commenced unloading rapidly.