By May 19, 1942, the Allies had begun to turn the tide in the Battle of the Atlantic. German submarines were achieving less and less in their effort to interrupt the flow of goods from America to England. Not only had Allied equipment and procedures improved to the point that escort ships were able to defend against submarines more effectively, aircraft were able to detect and attack submarines at greater distance from land.

Here is an account of one successful effort against submarine wolf packs.

A key element in increased Allied success was the effective use of communications intelligence, including code breaking and high frequency direction finding. By this time, all of the technical means of detecting and tracking submarines had improved to the point that German submarine operations had become very hazardous.

A significant organizational change occurred on May 20, with formation of the U.S. 10th Fleet, essentially a paper organization headquartered in Washington, DC.

Tenth Fleet's mission was to destroy enemy submarines, protect coastal merchant shipping, centralize control

and routing of convoys, and to coordinate and supervise all USN anti-submarine warfare

(ASW) training, anti-submarine intelligence, and coordination with Allied nations. The fleet was active from May 1943 to June 1945.

Tenth Fleet had no ships of its own, but used Commander-in-Chief Atlantic's ships operationally;

CinCLANT issued orders to escort groups originating in the

United States and organized and

operated hunter-killer groups built around the growing fleet of small Escort Aircraft Carriers. Tenth

Fleet never put to sea, had no ships, and never had more than about 50

people in its organization. The fleet was disbanded after the surrender

of Germany.

Showing posts with label navy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label navy. Show all posts

Sunday, May 19, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: May 19, 1943 - Battle of The Atlantic Turning Point

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: Isoroku Yamamoto

April 18, 1943, a squadron of US Army P-38 twin engine fighters took off from Guadalcanal on a 1,000 mile round-trip flight to shoot down a Japanese aircraft taking a very important person to Bougainville. The very important person was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese Fleet.

Four days earlier, US Navy communications intelligence personnel intercepted a series of messages encoded in the Japanese naval operating code, JN-25. It proved to be a series of communications giving Admiral Yamamoto's precise itinerary for a command inspection tour. The purpose of the tour was to enhance Japanese morale for their next planned offensive operations.

US planners considered what aircraft to assign to the mission. The only aircraft with enough range was the P-38. Eighteen P-38's were assigned to the mission, code-named Vengeance. The planned time of intercept was 09:35.

The four P-38's designated to intercept Yamamoto arrived at 09:34 just as Yamamoto's flight of two Japanese twin-engined aircraft began their descent. The interceptors shot down both aircraft. Yamamoto, in the lead aircraft, perished. Yamamoto's deputy, in the second aircraft, survived.

The mission was an assassination. The assassination succeeded. Today we would call it a "targeted killing."

Did it shorten the war or make the next two years of warfare easier? Probably not.

Four days earlier, US Navy communications intelligence personnel intercepted a series of messages encoded in the Japanese naval operating code, JN-25. It proved to be a series of communications giving Admiral Yamamoto's precise itinerary for a command inspection tour. The purpose of the tour was to enhance Japanese morale for their next planned offensive operations.

US planners considered what aircraft to assign to the mission. The only aircraft with enough range was the P-38. Eighteen P-38's were assigned to the mission, code-named Vengeance. The planned time of intercept was 09:35.

The four P-38's designated to intercept Yamamoto arrived at 09:34 just as Yamamoto's flight of two Japanese twin-engined aircraft began their descent. The interceptors shot down both aircraft. Yamamoto, in the lead aircraft, perished. Yamamoto's deputy, in the second aircraft, survived.

The mission was an assassination. The assassination succeeded. Today we would call it a "targeted killing."

Did it shorten the war or make the next two years of warfare easier? Probably not.

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: Battle Of Komandorski Islands

Did you ever hear about the Battle of Komandorski Islands? In brief, March 26 1943, RADM "Sock" McMorris took his task group out west of the Aleutian Islands to intercept a Japanese force enroute to reinforce the Japanese garrison on the island of Attu. It turned out the Japanese force was about twice as strong as McMorris' force.

The Americans got their noses bloodied, but they held off the Japanese force, who returned home without reinforcing Attu.

Here's a more complete account.

Just imagine fighting a battle that close to the Arctic.

The Americans got their noses bloodied, but they held off the Japanese force, who returned home without reinforcing Attu.

Here's a more complete account.

Just imagine fighting a battle that close to the Arctic.

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Small Wars In US History

Current media attention is focused on the war the United States started with Iraq a decade ago.

I'm reading an interesting book I picked up a couple of weeks ago at the Marine Corps Exchange at Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station: Just and Unjust Wars by Michel Walzer. The book's subtitle is "A Moral Argument With Historical Illustrations."

Just war theory focuses on two aspects of warfare: 1) was there a just cause (as in, was it justified or moral to initiate military action or respond with military action) and: 2) was the war conducted in a just manner.

I would say there is another aspect of war that does not strictly fall under just war theory, but it relates: was the war wise?

In the United States we have a fourth recurring question: was the war constitutional? Specifically, critics of particular wars often claim that the war is not legitimate, because Congress did not declare war as specified in the Constitution.

On this latter point, I recommend reading a really interesting military manual: Small Wars Manual United States Marine Corps 1940. The manual is available here. It is a clearly written guide to planning and conducting small wars in all of their variety.

Just read the introduction and it will be clear that what I have written elsewhere is true. Up to the time of World War II, most of our military interventions were conducted by the Department of the Navy. That included some very substantial military undertakings, including our Quasi-War with France during John Adams' administration. In no case was there ever a declaration of war when the conflict involved only the Navy Department.

Only when the War Department was involved in the conflict did the United States ever declare war. That has happened only five times in our history.

The fine line between conflicts involving only the Navy Department and categorized as "small wars" and the more substantial conflicts involving the War Department disappeared with passage in 1947 of the Armed Forces Unification Act.

That act created a constitutional muddle that we have never resolved.

We would be better off to return to a time when the Navy/Marine Corps team did small wars. They knew how to do it. A number of our military interventions would have been more competently planned and conducted if they had followed the 1940 Small Wars Manual of the Marine Corps.

It would save a lot of money, too.

I'm reading an interesting book I picked up a couple of weeks ago at the Marine Corps Exchange at Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station: Just and Unjust Wars by Michel Walzer. The book's subtitle is "A Moral Argument With Historical Illustrations."

Just war theory focuses on two aspects of warfare: 1) was there a just cause (as in, was it justified or moral to initiate military action or respond with military action) and: 2) was the war conducted in a just manner.

I would say there is another aspect of war that does not strictly fall under just war theory, but it relates: was the war wise?

In the United States we have a fourth recurring question: was the war constitutional? Specifically, critics of particular wars often claim that the war is not legitimate, because Congress did not declare war as specified in the Constitution.

On this latter point, I recommend reading a really interesting military manual: Small Wars Manual United States Marine Corps 1940. The manual is available here. It is a clearly written guide to planning and conducting small wars in all of their variety.

Just read the introduction and it will be clear that what I have written elsewhere is true. Up to the time of World War II, most of our military interventions were conducted by the Department of the Navy. That included some very substantial military undertakings, including our Quasi-War with France during John Adams' administration. In no case was there ever a declaration of war when the conflict involved only the Navy Department.

Only when the War Department was involved in the conflict did the United States ever declare war. That has happened only five times in our history.

The fine line between conflicts involving only the Navy Department and categorized as "small wars" and the more substantial conflicts involving the War Department disappeared with passage in 1947 of the Armed Forces Unification Act.

That act created a constitutional muddle that we have never resolved.

We would be better off to return to a time when the Navy/Marine Corps team did small wars. They knew how to do it. A number of our military interventions would have been more competently planned and conducted if they had followed the 1940 Small Wars Manual of the Marine Corps.

It would save a lot of money, too.

Topic Tags:

history,

military,

national security,

navy,

planning

Friday, February 22, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: USS Iowa (BB-61)

New York, NY: February 22, 1943. USS Iowa (BB-61) was commissioned at New York Naval Shipyard. The lead ship of the most powerful US battleships ever built, Iowa was a 45,000 -ton ship armed with nine 16-inch/50 caliber guns with a range of up to 24 miles, firing a projectile weighing up to 2,750 pounds. She also carried twenty 40-mm quadruple barrel Bofors anti-aircraft guns and twenty 5-inch/38 caliber dual-purpose guns arranged in twin mounts with a range of about 9 miles against surface targets. In addition, she bristled with 20-mm antiaircraft guns that proved of limited use and were removed right after the war.

| Class & type: | Iowa-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 45,000 tons |

| Length: | 887 ft 3 in (270.43 m) |

| Beam: | 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) |

| Draft: | 37 ft 2 in (11.33 m) |

| Speed: | 33 kn (38 mph; 61 km/h) |

| Complement: | 151 officers, 2637 enlisted |

| Armament: | 1943: 9 × 16 in (406 mm)/50 cal Mark 7 guns 20 × 5 in (127.0 mm)/38 cal Mark 12 guns 80 × 40 mm/56 cal anti-aircraft guns 49 × 20 mm/70 cal anti-aircraft cannons |

USS Iowa is the first ship I ever went to sea in during a midshipman training cruise to Europe during the summer of 1955.

Friday, February 8, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: The Week That Was

February 8, 1943, Japanese destroyer force (Rear Admiral Hashimoto Shintaro) completes the evacuation of 1,796 troops from Guadalcanal. The next day, February 9, 1943, US Army General Patch announced the end of organized Japanese resistance on the Island.

January 31, 1943, the German headquarters of the 6th Army at Stalingrad surrendered, including Field Marshall Paulus. Remaining scattered units surrendered February 2, ending the siege of Stalingrad.

To the north, on January 18, 1943, The Soviet Union established a land corridor iinto Leningrad, providing some relief for the siege of Leningrad, though it would be another year before the siege was completely broken.

Things were not going so well for the Allies in North Africa, but Germany was no longer able to reliably supply Rommel's forces. Rommel's forces would last for another three months.

There were to be no further Axis advances on any front.

January 31, 1943, the German headquarters of the 6th Army at Stalingrad surrendered, including Field Marshall Paulus. Remaining scattered units surrendered February 2, ending the siege of Stalingrad.

To the north, on January 18, 1943, The Soviet Union established a land corridor iinto Leningrad, providing some relief for the siege of Leningrad, though it would be another year before the siege was completely broken.

Things were not going so well for the Allies in North Africa, but Germany was no longer able to reliably supply Rommel's forces. Rommel's forces would last for another three months.

There were to be no further Axis advances on any front.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: Battle Of Rennell Island, Phase II

Dawn on January 30, 1942, found Admiral Giffen's Task Force 18 on its way back to Espiritu Santo. Their mission had not been completed. They did not rendezvous with the destroyer division from Tulagi, as had been planned. The resupply ships unloaded their supplies on Guadalcanal without the protection of TF 18.

Apparently Giffen lifted radio silence, because the previous night's disaster was reported to Adm Halsey in Noumea. At Halsey's direction, the two escort carriers kept a combat air patrol (CAP) on station over Chicago and Louisville all night long. He also ordered Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman's Enterprise carrier group to dd more CAP aircraft from dawn to dusk.

Halsey dispatched the tug Navajo and the destroyer transport Sands to go to Chicago's assistance. That afternoon, Halsey directed Giffen to return to Efate with the remaining battle worthy ships, turn the towing duties over to Navajo and rely on CAP to defend Chicago. Giffen took with him on Wichita the force's only trained fighter direction officer (FDO). Chicago had no practical way to control the CAP sent to their defense.

Four Grumman F4F's from Enterprise spotted a Japanes scout bomber and chased it for 40 miles, leaving Chicago unprotected. Eleven Japanese Bettys appeared over the horizon.

USS Enterprise, now only 40 miles south of Chicago, directed a flight of six F4F's to intercept the bombers, which appeared headed for Enterprise. The Japanese bombers immediately reversed course and headed for Chicago, which they believed to be a battleship. They identified the destroyer La Vallette, still standing by the cruiser and tug as a "Honolulu-class" cruiser. About 4:20 pm, nine Japanese bombers appeared out of the clouds and made their final approach in the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire.

At 4:24 one torpedo hit the starboard side forward, followed almost immediately with three torpedoes right where the ship had been hit the previous day. The captain ordered "abandon ship." At 4:43 pm the ship rolled to starboard and sank with her colors flying.

Navajo, Waller, Edwards and Sands picked up 1,069 survivors. La Vallette took one torpedo hit and survived.

Admiral Nimitz was irate when he learned that Chicago had been lost. He blamed Admiral Giffen. Giffens career survived, however, and he retired after the war as a Vice Admiral.

Chicago lost six officers and 55 enlisted men when the ship went down.

Chicago was the last ship lost in the struggle for Guadalcanal. By February 9, Japan had evacuated their last soldiers from the island.

This may have been the final "turning point" of the war. After this, Japan was fighting a rear guard action. The United States was busy replacing their lost ships, planes and sailors. Japan was not able to.

The cost of victory was high. For 2500 square miles of jungle, tall grass and sluggish rivers, the Allies had lost two fleet carriers, eight cruisers, 14 destroyers, numerous smaller vessels and aircraft, and over 6,000 lives: nearly 1600 Marines and soldiers, the rest - three times as many - Navy officers and men.

The cost of defeat was higher. Japan lost two battleships, a small carrier, four cruisers, 11 destroyers, and more than 23,000 men.

But they also lost any hope of victory.

Apparently Giffen lifted radio silence, because the previous night's disaster was reported to Adm Halsey in Noumea. At Halsey's direction, the two escort carriers kept a combat air patrol (CAP) on station over Chicago and Louisville all night long. He also ordered Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman's Enterprise carrier group to dd more CAP aircraft from dawn to dusk.

Halsey dispatched the tug Navajo and the destroyer transport Sands to go to Chicago's assistance. That afternoon, Halsey directed Giffen to return to Efate with the remaining battle worthy ships, turn the towing duties over to Navajo and rely on CAP to defend Chicago. Giffen took with him on Wichita the force's only trained fighter direction officer (FDO). Chicago had no practical way to control the CAP sent to their defense.

Four Grumman F4F's from Enterprise spotted a Japanes scout bomber and chased it for 40 miles, leaving Chicago unprotected. Eleven Japanese Bettys appeared over the horizon.

USS Enterprise, now only 40 miles south of Chicago, directed a flight of six F4F's to intercept the bombers, which appeared headed for Enterprise. The Japanese bombers immediately reversed course and headed for Chicago, which they believed to be a battleship. They identified the destroyer La Vallette, still standing by the cruiser and tug as a "Honolulu-class" cruiser. About 4:20 pm, nine Japanese bombers appeared out of the clouds and made their final approach in the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire.

At 4:24 one torpedo hit the starboard side forward, followed almost immediately with three torpedoes right where the ship had been hit the previous day. The captain ordered "abandon ship." At 4:43 pm the ship rolled to starboard and sank with her colors flying.

Navajo, Waller, Edwards and Sands picked up 1,069 survivors. La Vallette took one torpedo hit and survived.

Admiral Nimitz was irate when he learned that Chicago had been lost. He blamed Admiral Giffen. Giffens career survived, however, and he retired after the war as a Vice Admiral.

Chicago lost six officers and 55 enlisted men when the ship went down.

Chicago was the last ship lost in the struggle for Guadalcanal. By February 9, Japan had evacuated their last soldiers from the island.

This may have been the final "turning point" of the war. After this, Japan was fighting a rear guard action. The United States was busy replacing their lost ships, planes and sailors. Japan was not able to.

The cost of victory was high. For 2500 square miles of jungle, tall grass and sluggish rivers, the Allies had lost two fleet carriers, eight cruisers, 14 destroyers, numerous smaller vessels and aircraft, and over 6,000 lives: nearly 1600 Marines and soldiers, the rest - three times as many - Navy officers and men.

The cost of defeat was higher. Japan lost two battleships, a small carrier, four cruisers, 11 destroyers, and more than 23,000 men.

But they also lost any hope of victory.

Seventy Years Ago: Battle Of Rennell Island

The first six months of the war in the Pacific were fought mostly with ships, planes and men already in the Pacific when Pearl Harbor was attacked. They had been worked up to a high state of combat readiness by their fleet commander, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. Even after Kimmel was relieved of duty following the attack, the surviving forces acquitted themselves well.

The Pacific Fleet was hard pressed. They had lost four of their six large aircraft carriers in combat, and the remaining two, USS Saratoga and USS Enterprise, were just returning from extensive repair.

Some Pacific Fleet assets had been diverted to the Atlantic for the invasion of North Africa. That invasion now over, ships were moving through the Panama Canal to reinforce the Pacific.

That was the good news. The bad news is that the ships, their officers and their admirals weren't accustomed to operating in the Pacific. Not only was the tactical challenge different from the Atlantic, there was a less tangible difference of attitude.

The Atlantic Fleet was a "spit and polish" outfit. The Pacific Fleet was more a "get the job done" operation. That was especially true of the aviators and submariners.

| RADM Giffen's Formation |

RADM Robert C. "Ike" Giffen, a favorite of Atlantic Fleet Commander Admiral King, had just arrived in the Southwest Pacific with heavy cruiser USS Wichita and escort carriers Chenango and Suwanee, all having just completed the invasion of North Africa.

Giffen had experience against German submarines, but none against Japanese naval air forces. He also had very limited experience operating aircraft carriers. The two escort carriers were slow. Converted oilers, they could make no more than 18 knots. Worse than that, the wind was from the southeast, opposite from the direction Giffen needed to go.

Giffen had no concept of Japanese naval skills at operating both warships and aircraft at night.

Giffen's task force of three heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, eight destroyers and two escort carriers left Efate January 29. Destination: Guadalcanal by way of Rennell Island. Mission: Support a four-ship resupply mission for the marines, then sweep up through the "slot" to find and destroy Japanese ships.

Giffen ordered radio silence. Japanese submarines and aircraft tracked the force from the time it left Efate.

|

| Louisville Towing Chicago |

Under the circumstances, strict radio silence made little sense. The ships used their air and surface search radars, which the Japanese could detect at about the same range as the UHF radios used for line of sight communications. Most importantly, this order prevented the cruisers from communicating with the aircraft launched by the carriers.

Early the afternoon of January 29, Giffen worried that he wouldn't be at his rendezvous point on time. He ordered the two carriers, along with two destroyers, to continue at best speed, while the remainder of his force increased speed to 24 knots, remaining in a formation designed to protect against submarines rather than aircraft attack. Steaming at that speed increased the force's self noise so greatly as to render the sonar used to detect submarines nearly useless. It also announced the presence of the task force out to almost as great a distance as UHF radios would have.

Shortly after increasing speed, radar operators on the cruisers began picking up radar blips of unidentified aircraft ("bogies"). The US radars were equipped with an IFF feature to electronically distinguish friend from foe, but operators deemed it unreliable. To find out whether the radar blips were friendly or hostile aircraft would have required fighter-director personnel to send aircraft from the carriers to visually identify the aircraft. But they couldn't do so because of radio silence.

Radio silence made no sense.

At sunset, Giffen ceased zigzagging his force and proceeded on a set course to his rendezvous. The bogies were about sixty miles to the west, approaching fast. They were in fact hostile, Japanese twin-engine land-based bombers, armed with torpedoes. The Bettys maneuvered around Giffen's force and attacked from the east, where they sky was dark, but with Giffen's ships silhouetted against the evening twilight.

Giffen's ships put up a barrage of anti-aircraft fire, and the first wave of bombers did not damage any of the ships. USS Louisville was struck by a dud torpedo, but there was no damage. Giffen issued no orders, and the force continued as before.

A second Japanese air group dropped flares alongside Giffen's cruisers in the moonless night. At 7:38 pm, the lead Betty crashed in flames off USS Chicago's port bow, brightly silhouetting the ship for the following aircraft.

One air launched torpedo hit Chicago in the starboard side, flooding the after fire room. Two minutes later, another torpedo hit at number three fireroom. Three of the ship's four shafts stopped turning, the rudder jammed, and soon the ship was dead in the water. Another torpedo hit the flagship Wichita but did not explode.

Chicago's crew managed to control flooding with the list at 11 degrees. At first, they had only electrical power from the emergency diesel generator. Soon they were able to relight one boiler and generate more electricity to use more powerful pumps.

Giffen ordered USS Louisville to take Chicago in tow. By midnight, The tow was underway at three knots, headed for Espiritu Santo.

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: Eleanor Roosevelt's Diary

January 22, 1943, Eleanor Roosevelt travels from Washington to Christen the new USS Yorktown. She christened the first one in 1936 at Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock. As Mrs. Roosevelt explained, Yorktown (CV-5) gave a good account of herself in the war, but was lost at the battle of Midway. Now she was to christen the second one, USS Yorktown (CV-10), the second new large aircraft carrier of the Essex class, also built at Newport News. Here are Mrs. Roosevelt's thoughts on that occasion about the US shipbuilders.

The second Yorktown had a distinguished record in World War II, Korea, Viet Nam and in the Apollo program. She is still afloat, having been decommissioned in 1970 and in 1975 becoming a museum ship at Patriot's Point, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She is a National Historic Landmark.

The second Yorktown had a distinguished record in World War II, Korea, Viet Nam and in the Apollo program. She is still afloat, having been decommissioned in 1970 and in 1975 becoming a museum ship at Patriot's Point, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She is a National Historic Landmark.

Saturday, January 5, 2013

Seventy Years Ago: VT Projectiles Shoot Down Japanese Dive Bomber

January 5, 1943. Task Group 67.2 (Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth) bombards a Japanese airfield and installations at Munda, New Georgia, Solomons Islands. After the rest of Task Force 67 joins TG 67.2, Japanese planes attack the force, just missing light cruiser Honolulu (CL 48) and damaging New Zealand light cruiser HMNZS Achilles, 18 miles south of Cape Hunter, Guadalcanal. In the action, light cruiser Helena (CL 50) becomes the first U.S. Navy ship to use 5 inch/38 caliber Mk. 32 proximity-fuzed projectiles in combat, downing a Japanese Aichi Type 99 carrier bomber (VAL) with her second salvo

This was a major technological triumph. These 5-inch projectiles contained a tiny radio proximity device, essentially a miniature radar, which caused the projectile to explode if it came close enough to the airplane to do damage. This system, under development since mid-1940, was a vast improvement over the mechanical time fuze previously used against aircraft. It also replaced contact fuzes that had to actually hit the aircraft to explode.

To conceal the purpose of the projectiles, they were designated as "VT-Fuzed projectiles" (Variable-Time fuze).

The story of development of the proximity fuze is detailed here in an article on the Naval Historical Center web site.

The greatest challenge was to ruggedize the miniature electronic tubes used in the circuitry back in the day before transistors.

Mark 53 Proximity Fuze

Monday, December 31, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: War In The Pacific

December 31, 1942. The Japanese military high command decides to evacuate forces from Guadalcanal. It will be a complex and challenging undertaking to withdraw forces, and will take more than a month. There will be more battles.

USS Essex, lead ship of a more powerful class of aircraft carriers, is commissioned today.

On New Guinea, after more than two months of jungle fighting against well-defended Japanese positions, the US Army I Corps was nearing victory at Buna on the north coast of New Guinea. Victory here will relieve pressure on Port Moresby.

USS Essex, lead ship of a more powerful class of aircraft carriers, is commissioned today.

On New Guinea, after more than two months of jungle fighting against well-defended Japanese positions, the US Army I Corps was nearing victory at Buna on the north coast of New Guinea. Victory here will relieve pressure on Port Moresby.

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Pacific Fleet Carriers

December, 1942, the US Navy's force of aircraft carriers was depleted. Of the seven carriers in service at the time of Pearl Harbor, only USS Ranger, smallest and slowest of the seven, remained undamaged. She was also the only one of the seven serving in the Atlantic Fleet.

The Pacific Fleet had lost Lexington, Yorktown, Hornet and Wasp. That left only Saratoga, twice torpedoed and repaired and Enterprise, damaged at the Battle of Coral Sea,and bombed six times later in the year.

Relief was at hand.

USS Essex, prototype of a newer, more powerful class of carriers, was to be commissioned in two days - December 31, 1942. Two weeks later, USS Independence, prototype of a smaller carrier built on a cruiser hull, was to be commissioned. Independence carried fewer aircraft, but was as fast as the larger Enterprise and Saratoga.

There would be nine new Independence class carriers in service by the end of 1943, almost one a month entering service. Only one, USS Princeton, was sunk in combat.

But the backbone of the Pacific Fleet was to be the Essex class. Thirty-two were ordered. Twenty-four were completed by war's end.None was lost in combat.

The Pacific Fleet had lost Lexington, Yorktown, Hornet and Wasp. That left only Saratoga, twice torpedoed and repaired and Enterprise, damaged at the Battle of Coral Sea,and bombed six times later in the year.

Relief was at hand.

USS Essex, prototype of a newer, more powerful class of carriers, was to be commissioned in two days - December 31, 1942. Two weeks later, USS Independence, prototype of a smaller carrier built on a cruiser hull, was to be commissioned. Independence carried fewer aircraft, but was as fast as the larger Enterprise and Saratoga.

There would be nine new Independence class carriers in service by the end of 1943, almost one a month entering service. Only one, USS Princeton, was sunk in combat.

But the backbone of the Pacific Fleet was to be the Essex class. Thirty-two were ordered. Twenty-four were completed by war's end.None was lost in combat.

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Japanese Carrier Ryuho

At 0915, December 12, 1942, Japanese Light Aircraft Carrier steaming near Hachijo Jima off the coast of Japan, was torpedoed by USS Drum. Ryuho had left the previous day on her first mission, loaded with 20 light bombers on a ferry mission, her very first operation. She was a converted submarine tender, whose conversion was completed November 30.

It was the second time Ryuho was damaged by US forces. April 18, 1942, during the Doolittle raid on Japan, one of the B-25's hit Ryuho with a 500 pound bomb and some small incendiary weapons. The ship was in drydock at Yokosuka naval base. The damage delayed her completion.

It was the second time Ryuho was damaged by US forces. April 18, 1942, during the Doolittle raid on Japan, one of the B-25's hit Ryuho with a 500 pound bomb and some small incendiary weapons. The ship was in drydock at Yokosuka naval base. The damage delayed her completion.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: First Year Of The Pacific War

The war had been going on for a year. It was mostly a naval war.

If the war were scored like a game of checkers, you would conclude that Japan was ahead. But Japan had made no significant advances since the early weeks. Repeated attempts to take control of Papua New Guinea had failed. Japan was hanging on to Buna, Salamaua and Lae on the northern coast by their fingernails.

Japanese soldiers on Guadalcanal had been unable to expel US Marines. The Japanese navy was unable to supply troops with food, much less with ammunition.

But fierce battles at sea had been costly to both sides. The score in ships sunk:

Warship losses in the First Year of the Pacific War.

If the war were scored like a game of checkers, you would conclude that Japan was ahead. But Japan had made no significant advances since the early weeks. Repeated attempts to take control of Papua New Guinea had failed. Japan was hanging on to Buna, Salamaua and Lae on the northern coast by their fingernails.

Japanese soldiers on Guadalcanal had been unable to expel US Marines. The Japanese navy was unable to supply troops with food, much less with ammunition.

But fierce battles at sea had been costly to both sides. The score in ships sunk:

Warship losses in the First Year of the Pacific War.

| U.S. | Allies | Japanese | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battleships | 2 | 2 RN | 2 |

| Fleet Carriers | 4 | - | 4 |

| Light Carriers | - | 1 RN | 2 |

| Heavy Cruisers | 5 | 3 RN , 1 Aus | 4 |

| Light Cruisers | 2 | 2 Dutch, 1 Aus | 2 |

| Destroyers | 23 | 8 Dutch, 7+3 RN. 2+2 Aus | 26 |

| Submarines | 7 | 5 Dutch | 21 |

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Battle Of Tassafaronga

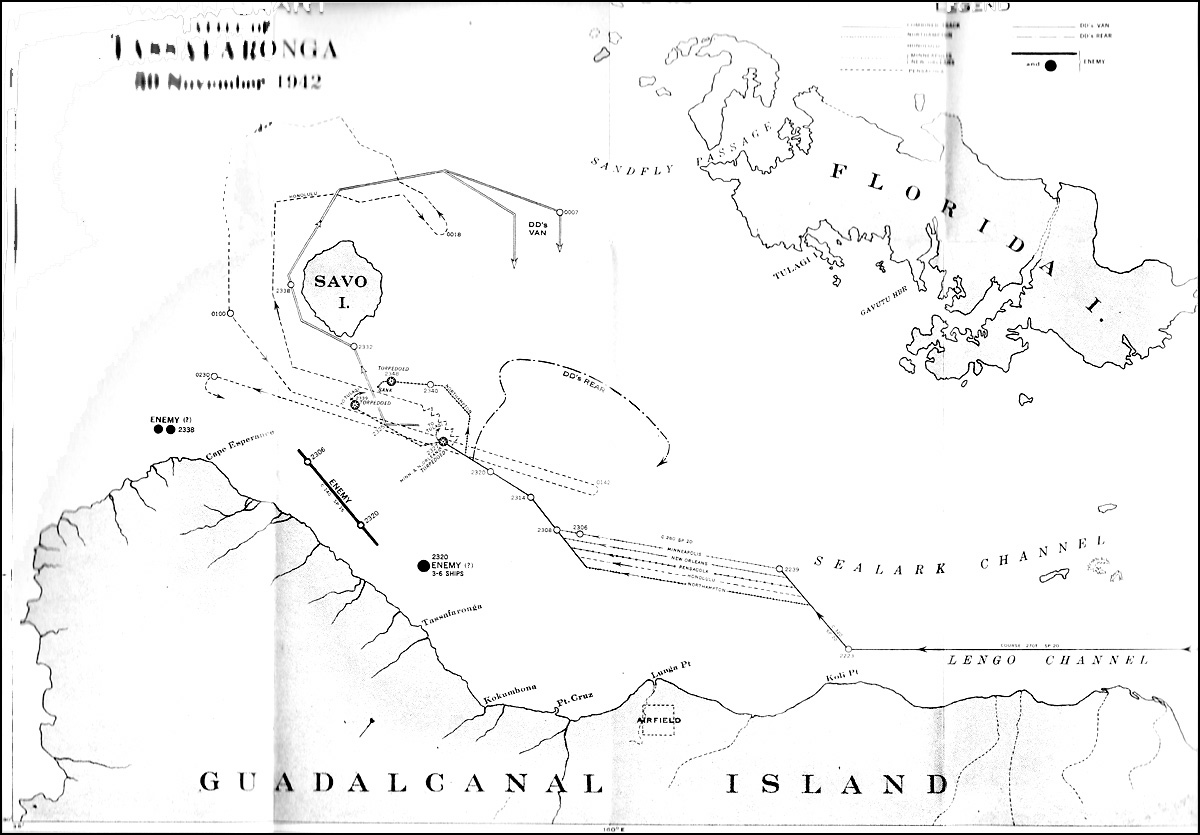

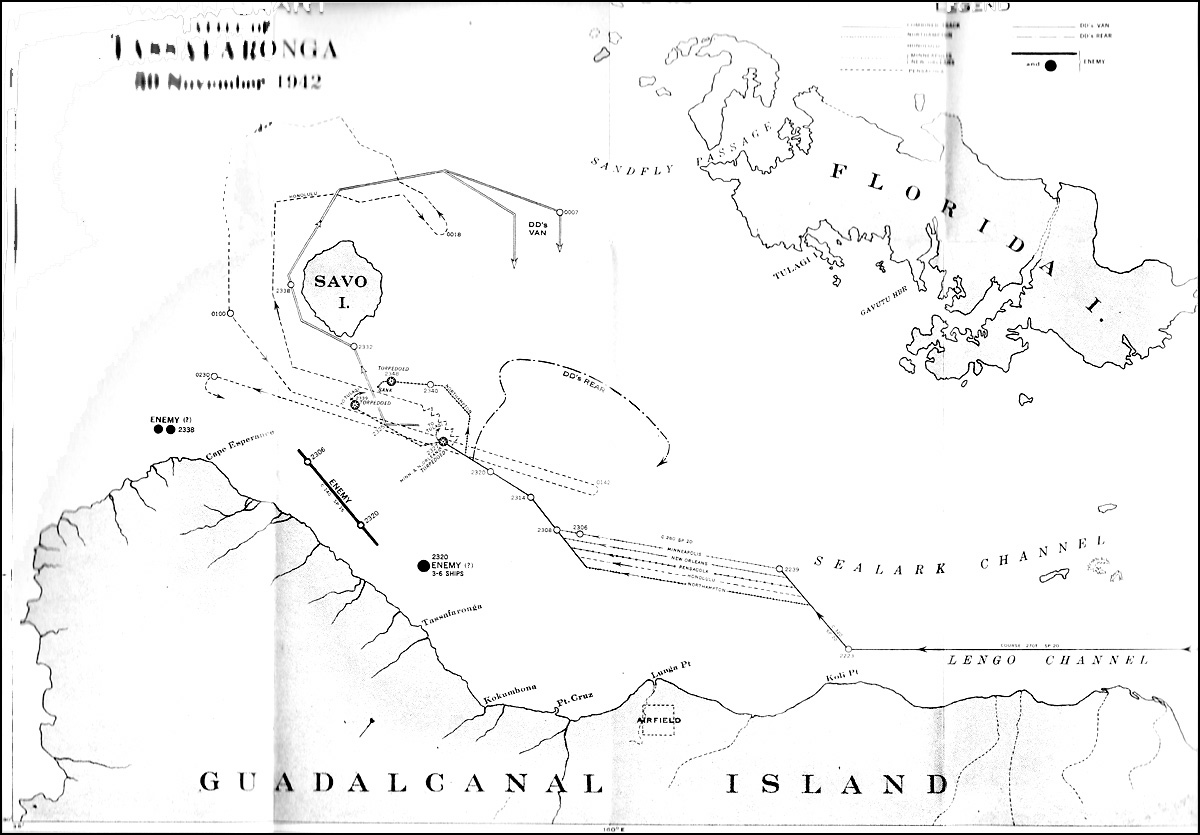

Japanese Army forces on Guadalcanal were desperately short of food and on November 26, 1942, radioed pleading for more. The previous three weeks, only submarines had been able to deliver supplies. Each submarine delivered about a days' supply, but the difficulty of offloading and delivering the food through the jungle reduced what reached the troops. The troops were living on one-third rations.

Japan had resorted to submarines because they were unable to rely on surface ships. A combination of US aircraft operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, US PT Boats operating from Tulagi and US surface warships had prevented Japanese resupply operations by ship.

The Japanese developed a new plan. Resupply by high speed destroyers carrying floating drums of food and medical supplies. The drums, connected to each other by line, were to be carried on the decks of six destroyers, escorted by two more. The destroyers would approach at high speed, drop the drums overboard and return to base. Soldiers would swim out and recover the drums.

Following the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Admiral Halsey, Commander of the Southern Pacific Command, reorganized his surface warfare forces, forming a new Task Force, TF 67, at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, about 580 miles from Guadalcanal. The Task Force, initially under RADM Kinkaid, was reassigned to RADM Carleton H. Wright on November 28.

TF 67's job: intercept and destroy any Japanese surface force coming to the aid of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

The U.S. victory at the Battle of Guadalcanal had cost Halsey 18 ships sunk or so badly damaged that extensive repairs were required. With the exception of destroyers, Halsey's only available surface units were the carrier Enterprise, the battleship Washington, and the light cruiser San Diego at Noumea and the heavy cruisers Northampton and Pensacola at Espiritu Santo.

Several other ships were en route to the South Pacific. By 25 November, as intelligence was piecing together a clearer picture of Japanese plans, Halsey had assembled a force adequate to counter the expected offensive. At Nandi in the Fijis lay the carrier Saratoga, the battleships North Carolina, Colorado, and Maryland, and the light cruiser San Juan. The heavy cruisers New Orleans, Northampton, and Pensacola, and the light cruiser Honolulu were stationed at Espiritu Santo. These last two, together with the heavy cruiser Minneapolis which arrived on the 27th, had come from Pearl Harbor. Here also on the 27th were the destroyers Drayton (which had accompanied the Minneapolis), Fletcher Maury, and Perkins.

On 27 November, these 5 cruisers and 4 destroyers at Espiritu Santo were grouped in to a separate task force, Task Force William, under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, with general instructions from Halsey to intercept any Japanese surface forces approaching Guadalcanal. Admiral Kinkaid prepared a detailed set of operational orders for the Force, but, before he could go over them with his captains, he was ordered to other duty. He was replaced by Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, who had just made port in the Minneapolis.

Task Force William consisted of four heavy cruisers: Minneapolis, New Orleans, Northampton and Pensacola. Admiral Wright was embarked in Minneapolis;

One light cruiser: Honolulu, with RADM Tisdale embarked; Four destroyers: Drayton, Fletcher, Maury, Perkins. USS Fletcher was the fleet's newest and most powerful destroyer. Her CO, Commander William M. Cole, was in charge of the destroyer unit.

On 29 November the Task Force was moored at Espiritu Santo on 12 hours notice for getting underway. Admiral Wright held a conference, attended by Admiral Tisdale and the commanding officers of the 9 ships, at which the operation plan drawn up by Admiral Kinkaid was "briefly discussed."

At 1940 Admiral Wright received orders to prepare to depart with his force at the earliest possible moment, and to proceed at the best possible speed to intercept an enemy group of 6 destroyers and 6 transports which was expected to arrive off Guadalcanal the next night. He directed Task Force WILLIAM to make all preparations necessary to get under way immediately, and advised COMSOPAC that his ships would be ready to sortie at midnight.

Three hours later COMSOPAC ordered Admiral Wright to proceed with all available units, pass through Lengo Channel (between Guadalcanal and Florida Islands), and intercept the Japanese off Tassafaronga on the northwestern shore of Guadalcanal. Later, Admiral Wright received information that enemy combatant ships might be substituted for the transports, or that the Japanese force might consist wholly of destroyers, and that a hostile landing might be attempted off Tassafaronga earlier than 2300, 30 November. He received no further advices respecting the size or composition of the opposing units.

Admiral Wright promptly put into effect, with minor modifications, Admiral Kinkaid's operation plan, and set midnight as the zero hour for his ships to sortie. Actually the destroyers got under way at 2310, the cruisers at 2335. The whole Force cleared the well-mined, unlighted harbor of Espiritu Santo without incident and shaped its course to pass northeast of San Cristobal Island.

Task Force WILLIAM cleared Lengo Channel at 2225 at a speed of 20 knots. Its average speed made good from midnight, 29 November, when it left Espiritu Santo until it entered Lengo Channel at 2140, 30 November, was 28.2 knots. The cruisers steamed in column, 1,000 yards apart, while the destroyers in the van bore 300° T., 4,000 yards from the Minneapolis. The night was very dark, the sky completely overcast. Maximum surface visibility was not over 2 miles.

Admiral Wright had prepositioned sea planes from the cruisers at Tulagi. Their instructions were to take off in time to patrol the area between Cape Esperance and Lunga Point starting at 2200. They carried flares to drop at Admiral Wright's command. The rest of Admiral Wright's plan depended on using the Navy's new SG surface search radar to gain the advantage of surprise. The four destroyers were in the van (ahead), followed by the cruisers steaming in column 1,000 yards apart. Two additional destroyers, Lamson and Lardner, joined the force at 2100, bringing up the rear. Lamson's CO, Commander Abercrombie, was senior to Cole, but had no copies of the plan, no surface radar, and no knowledge of what was going on. He was therefore unable to assume command of the destroyer force.

At 2306, Minneapolis' SG radar picks up two objects off Cape Esperance. At 2316, Cdr Cole, in accordance with the plan, requested permission to launch torpedo attack on enemy formation of 5 ships, distant 7,000 yards.

About 2321, Admiral Wright ordered ships to commence firing star shells (for illumination) and explosive shells. Apparently TF 67 had caught the Japanese by surprise. The force engaged eight Japanese destroyers or cruisers using fire control radar for aiming. After a few minutes, four of the radar targets disappeared from the radar and some were visually seen to explode and sink.

There was some confusion in attempts to correlate ranges and bearings of Japanese ships, but as of 2326, it appeared that TF67 had won a great victory.

At 2327 a Japanese torpedo struck Minneapolis', blowing off her bow. The ship kept firing until her engineering plant failed and lost power. At 2328, New Orleans was torpedoed, losing her bow as far aft as Turret II. At 2329, a torpedo struck Pensacola on the port side aft, the ship erupted in flames, and fire raged for hours. At 2348, Northampton was torpedoed. Despite valiant efforts to save her, she finally sank about 0300.

Thus, within a few minutes, what had seemed a great victory turned into a resounding loss. One US heavy cruiser sunk, three out of action for months, 395 sailors killed.

As it turned out, only one Japanese destroyer was lost and 197 killed.

Even so, TF67 succeeded in preventing Japanese resupply of their troops on Guadalcanal.

The battle revealed continuing shortcomings in the use of radar.

The surface force was not yet aware that reliability problems affecting submarine torpedoes also applied to those launched by surface ships. Corrective action was many months away.

But damage control and firefighting crews performed magnificently. It is almost inconceivable that Minneapolis, New Orleans and Pensacola were saved and lived to fight another day.

The US Navy still did not know how powerful and effective Japanese type 93 surface-launched torpedoes were. Admiral Wright, in his after action report, still thought the sips had been torpedoed by undetected submarines. There were, after all, no Japanese surface ships within what we believed to be torpedo range.

We would not learn of their technological superiority until later in 1943, when intact torpedoes were captured.

Japan had resorted to submarines because they were unable to rely on surface ships. A combination of US aircraft operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, US PT Boats operating from Tulagi and US surface warships had prevented Japanese resupply operations by ship.

The Japanese developed a new plan. Resupply by high speed destroyers carrying floating drums of food and medical supplies. The drums, connected to each other by line, were to be carried on the decks of six destroyers, escorted by two more. The destroyers would approach at high speed, drop the drums overboard and return to base. Soldiers would swim out and recover the drums.

Following the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Admiral Halsey, Commander of the Southern Pacific Command, reorganized his surface warfare forces, forming a new Task Force, TF 67, at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, about 580 miles from Guadalcanal. The Task Force, initially under RADM Kinkaid, was reassigned to RADM Carleton H. Wright on November 28.

TF 67's job: intercept and destroy any Japanese surface force coming to the aid of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

The U.S. victory at the Battle of Guadalcanal had cost Halsey 18 ships sunk or so badly damaged that extensive repairs were required. With the exception of destroyers, Halsey's only available surface units were the carrier Enterprise, the battleship Washington, and the light cruiser San Diego at Noumea and the heavy cruisers Northampton and Pensacola at Espiritu Santo.

Several other ships were en route to the South Pacific. By 25 November, as intelligence was piecing together a clearer picture of Japanese plans, Halsey had assembled a force adequate to counter the expected offensive. At Nandi in the Fijis lay the carrier Saratoga, the battleships North Carolina, Colorado, and Maryland, and the light cruiser San Juan. The heavy cruisers New Orleans, Northampton, and Pensacola, and the light cruiser Honolulu were stationed at Espiritu Santo. These last two, together with the heavy cruiser Minneapolis which arrived on the 27th, had come from Pearl Harbor. Here also on the 27th were the destroyers Drayton (which had accompanied the Minneapolis), Fletcher Maury, and Perkins.

On 27 November, these 5 cruisers and 4 destroyers at Espiritu Santo were grouped in to a separate task force, Task Force William, under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, with general instructions from Halsey to intercept any Japanese surface forces approaching Guadalcanal. Admiral Kinkaid prepared a detailed set of operational orders for the Force, but, before he could go over them with his captains, he was ordered to other duty. He was replaced by Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, who had just made port in the Minneapolis.

Task Force William consisted of four heavy cruisers: Minneapolis, New Orleans, Northampton and Pensacola. Admiral Wright was embarked in Minneapolis;

One light cruiser: Honolulu, with RADM Tisdale embarked; Four destroyers: Drayton, Fletcher, Maury, Perkins. USS Fletcher was the fleet's newest and most powerful destroyer. Her CO, Commander William M. Cole, was in charge of the destroyer unit.

On 29 November the Task Force was moored at Espiritu Santo on 12 hours notice for getting underway. Admiral Wright held a conference, attended by Admiral Tisdale and the commanding officers of the 9 ships, at which the operation plan drawn up by Admiral Kinkaid was "briefly discussed."

At 1940 Admiral Wright received orders to prepare to depart with his force at the earliest possible moment, and to proceed at the best possible speed to intercept an enemy group of 6 destroyers and 6 transports which was expected to arrive off Guadalcanal the next night. He directed Task Force WILLIAM to make all preparations necessary to get under way immediately, and advised COMSOPAC that his ships would be ready to sortie at midnight.

Three hours later COMSOPAC ordered Admiral Wright to proceed with all available units, pass through Lengo Channel (between Guadalcanal and Florida Islands), and intercept the Japanese off Tassafaronga on the northwestern shore of Guadalcanal. Later, Admiral Wright received information that enemy combatant ships might be substituted for the transports, or that the Japanese force might consist wholly of destroyers, and that a hostile landing might be attempted off Tassafaronga earlier than 2300, 30 November. He received no further advices respecting the size or composition of the opposing units.

Admiral Wright promptly put into effect, with minor modifications, Admiral Kinkaid's operation plan, and set midnight as the zero hour for his ships to sortie. Actually the destroyers got under way at 2310, the cruisers at 2335. The whole Force cleared the well-mined, unlighted harbor of Espiritu Santo without incident and shaped its course to pass northeast of San Cristobal Island.

Task Force WILLIAM cleared Lengo Channel at 2225 at a speed of 20 knots. Its average speed made good from midnight, 29 November, when it left Espiritu Santo until it entered Lengo Channel at 2140, 30 November, was 28.2 knots. The cruisers steamed in column, 1,000 yards apart, while the destroyers in the van bore 300° T., 4,000 yards from the Minneapolis. The night was very dark, the sky completely overcast. Maximum surface visibility was not over 2 miles.

Admiral Wright had prepositioned sea planes from the cruisers at Tulagi. Their instructions were to take off in time to patrol the area between Cape Esperance and Lunga Point starting at 2200. They carried flares to drop at Admiral Wright's command. The rest of Admiral Wright's plan depended on using the Navy's new SG surface search radar to gain the advantage of surprise. The four destroyers were in the van (ahead), followed by the cruisers steaming in column 1,000 yards apart. Two additional destroyers, Lamson and Lardner, joined the force at 2100, bringing up the rear. Lamson's CO, Commander Abercrombie, was senior to Cole, but had no copies of the plan, no surface radar, and no knowledge of what was going on. He was therefore unable to assume command of the destroyer force.

At 2306, Minneapolis' SG radar picks up two objects off Cape Esperance. At 2316, Cdr Cole, in accordance with the plan, requested permission to launch torpedo attack on enemy formation of 5 ships, distant 7,000 yards.

About 2321, Admiral Wright ordered ships to commence firing star shells (for illumination) and explosive shells. Apparently TF 67 had caught the Japanese by surprise. The force engaged eight Japanese destroyers or cruisers using fire control radar for aiming. After a few minutes, four of the radar targets disappeared from the radar and some were visually seen to explode and sink.

There was some confusion in attempts to correlate ranges and bearings of Japanese ships, but as of 2326, it appeared that TF67 had won a great victory.

At 2327 a Japanese torpedo struck Minneapolis', blowing off her bow. The ship kept firing until her engineering plant failed and lost power. At 2328, New Orleans was torpedoed, losing her bow as far aft as Turret II. At 2329, a torpedo struck Pensacola on the port side aft, the ship erupted in flames, and fire raged for hours. At 2348, Northampton was torpedoed. Despite valiant efforts to save her, she finally sank about 0300.

Thus, within a few minutes, what had seemed a great victory turned into a resounding loss. One US heavy cruiser sunk, three out of action for months, 395 sailors killed.

As it turned out, only one Japanese destroyer was lost and 197 killed.

Even so, TF67 succeeded in preventing Japanese resupply of their troops on Guadalcanal.

The battle revealed continuing shortcomings in the use of radar.

The surface force was not yet aware that reliability problems affecting submarine torpedoes also applied to those launched by surface ships. Corrective action was many months away.

But damage control and firefighting crews performed magnificently. It is almost inconceivable that Minneapolis, New Orleans and Pensacola were saved and lived to fight another day.

New Orleans at Tulagi

Minneapolis at Tulagi

The US Navy still did not know how powerful and effective Japanese type 93 surface-launched torpedoes were. Admiral Wright, in his after action report, still thought the sips had been torpedoed by undetected submarines. There were, after all, no Japanese surface ships within what we believed to be torpedo range.

We would not learn of their technological superiority until later in 1943, when intact torpedoes were captured.

Thursday, November 15, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Naval Battle Of Guadalcanal, Phase II

The first phase, November 12-13 of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal had resulted in the deaths of US Admirals Scott and Callaghan and the loss of two light cruisers and four destroyers. Japan lost battleship Hiei, two destroyers and seven transports.

Admiral Abe withdrew his forces, including his remaining battleship, Kirishima one light cruiser and eleven destroyers. Yamamoto postponed the planned Japanese landing on Guadalcanal until November 15.

The US had paid a high price for a two-day delay. Callaghan's forces thought they had won a great victory. Subsequent analysis revealed that Callaghan's force disposition failed to make best use of the capabilities of radar, with which he was unfamiliar, and that he had issued unclear and confusing orders.

The truth is, that once again Japanese training in night combat operations and superior Japanese torpedoes had inflicted a tactical defeat on American forces.

Strategically, Callaghan and Scott had turned back the Japanese invasion force.

Japan remained committed to reinforcing their troops on Guadalcanal and pushing the Americans off the island. They started the force back toward Guadalcanal, with battleship Kirishima, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and nine destroyers under command of Rear Admiral Kondo.

Halsey had few undamaged forces to send in to the fray. He dare not send the damaged Enterprise into a night time engagement. But he decided to send most of Enterprise's escorts, including four destroyers and the fleet's newest battleships, USS South Dakota (BB-57) and USS Washington (BB-58) under command of Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, embarked in Washington.

Admiral Lee understood radar. He also understood tactics. He spent much of the evening of November 14 discussing how to use the ship's radar with Washington's commanding officer and gunnery officer. They knew what to do.

About 2300 that evening, Washington and South Dakota radars detected the Japanese forces, now under command of Admiral Kondo, in the vicinity of Savo Island. All ships were at general quarters (battle stations) and expecting action.

A few minutes after spotting the Japanese force, both Washington and South Dakota opened fire. The four US destroyers engaged the Japanese cruisers. Within minutes, two were sunk by Japanese torpedoes, a third had lost her bow, and the fourth took a hit in the engine room, taking her out of the action.

That left two new, untried battleships in defense of Guadalcanal.

The Japanese spotted South Dakota and brought all their guns to bear. Between midnight and 0030, the battleship was hit by 26 Japanese projectiles, none of which penetrated her armor. But about that time, South Dakota suffered a series of electrical failures, rendering her blind (no radar), dumb (no radio communications) and somewhat lame, though she suffered no major structural damage. She steered away from the action, in the direction of a previously agreed rendezvous point.

The electrical failures may have been caused by failure of automatic bus transfer switches (ABT) to work properly. Similar failures may have contributed to loss of Yorktown at Midway.

In any event, this left USS Washington alone against a Japanese battleship, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and as many as nine destroyers still effective. The Japanese were still concentrating their fire on South Dakota and failed to spot Washington as she approached the action.

Once Admiral Lee was certain who was friend and foe, Washington opened fire on Kirishima at a range of about 9,000 yards. Kirishima and the destroyer Ayanami were badly damaged and burning. Both ships were scuttled and abandoned about 0325.

Believing the way clear for the invasion force, Kondo withdrew his remaining ships

The four Japanese transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal by 04:00 on 15 November, and the escort destroyers raced back up the Slot toward safer waters. Aircraft from Henderson field attacked the transports beginning about 0600, joined by field artillery from ground forces. Only 2,000–3,000 of the Japanese troops originally embarked actually made it to Guadalcanal, and most of their ammunition and food supplies were lost.

This was the last major attempt by Japan to establish control of the seas around Guadalcanal and to retake the island, though there would be more skirmishes.

Admiral Abe withdrew his forces, including his remaining battleship, Kirishima one light cruiser and eleven destroyers. Yamamoto postponed the planned Japanese landing on Guadalcanal until November 15.

The US had paid a high price for a two-day delay. Callaghan's forces thought they had won a great victory. Subsequent analysis revealed that Callaghan's force disposition failed to make best use of the capabilities of radar, with which he was unfamiliar, and that he had issued unclear and confusing orders.

The truth is, that once again Japanese training in night combat operations and superior Japanese torpedoes had inflicted a tactical defeat on American forces.

Strategically, Callaghan and Scott had turned back the Japanese invasion force.

Japan remained committed to reinforcing their troops on Guadalcanal and pushing the Americans off the island. They started the force back toward Guadalcanal, with battleship Kirishima, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and nine destroyers under command of Rear Admiral Kondo.

Halsey had few undamaged forces to send in to the fray. He dare not send the damaged Enterprise into a night time engagement. But he decided to send most of Enterprise's escorts, including four destroyers and the fleet's newest battleships, USS South Dakota (BB-57) and USS Washington (BB-58) under command of Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, embarked in Washington.

Admiral Lee understood radar. He also understood tactics. He spent much of the evening of November 14 discussing how to use the ship's radar with Washington's commanding officer and gunnery officer. They knew what to do.

About 2300 that evening, Washington and South Dakota radars detected the Japanese forces, now under command of Admiral Kondo, in the vicinity of Savo Island. All ships were at general quarters (battle stations) and expecting action.

A few minutes after spotting the Japanese force, both Washington and South Dakota opened fire. The four US destroyers engaged the Japanese cruisers. Within minutes, two were sunk by Japanese torpedoes, a third had lost her bow, and the fourth took a hit in the engine room, taking her out of the action.

That left two new, untried battleships in defense of Guadalcanal.

The Japanese spotted South Dakota and brought all their guns to bear. Between midnight and 0030, the battleship was hit by 26 Japanese projectiles, none of which penetrated her armor. But about that time, South Dakota suffered a series of electrical failures, rendering her blind (no radar), dumb (no radio communications) and somewhat lame, though she suffered no major structural damage. She steered away from the action, in the direction of a previously agreed rendezvous point.

The electrical failures may have been caused by failure of automatic bus transfer switches (ABT) to work properly. Similar failures may have contributed to loss of Yorktown at Midway.

In any event, this left USS Washington alone against a Japanese battleship, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and as many as nine destroyers still effective. The Japanese were still concentrating their fire on South Dakota and failed to spot Washington as she approached the action.

Once Admiral Lee was certain who was friend and foe, Washington opened fire on Kirishima at a range of about 9,000 yards. Kirishima and the destroyer Ayanami were badly damaged and burning. Both ships were scuttled and abandoned about 0325.

Believing the way clear for the invasion force, Kondo withdrew his remaining ships

The four Japanese transports beached themselves at Tassafaronga on Guadalcanal by 04:00 on 15 November, and the escort destroyers raced back up the Slot toward safer waters. Aircraft from Henderson field attacked the transports beginning about 0600, joined by field artillery from ground forces. Only 2,000–3,000 of the Japanese troops originally embarked actually made it to Guadalcanal, and most of their ammunition and food supplies were lost.

This was the last major attempt by Japan to establish control of the seas around Guadalcanal and to retake the island, though there would be more skirmishes.

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Naval Battle Of Guadalcanal

For almost three months, Japanese forces had tried mightily to dislodge the Marines from Guadalcanal, without success. Every Japanese effort to reinforce their army forces on the island had been thwarted or at least limited by the US Navy.

Japan had achieved major successes against the US Navy, including submarine attacks on USS Saratoga and battleship North Carolina, under repair at Pearl Harbor. In late October, Japan sank the carrier USS Hornet and thought they might have sunk Enterprise. Now they planned to send a powerful surface force to bombard Henderson Field, where the "Cactus Air Force" of Marine, Navy and Army aircraft continued to operate with deadly effect against Japanese naval forces trying to reinforce Guadalcanal.

The night of November 12/13, 1942, the Japanese bombardment force under Admiral Abe approached the area, passing south of Savo Island, with two battleships, a light cruiser and thirteen escorting destroyers. The battleships were armed with high explosive projectiles to do maximum damage against the aircraft and fuel dumps at Henderson Field. Such projectiles would be of limited use against battleships and heavy cruisers, but Abe expected no opposition.

The Enterprise had not been sunk. She was undergoing urgent repair at the harbor of Noumea. Her formation was still a powerful force: the fast battleships Washington and South Dakota, the heavy cruiser Northampton, the light cruiser San Diego and six destroyers were protecting her.

At Espiritou Santo, moreover, Halsey retained Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner's transport units, to conduct another supply run to be completed by 12 November. In his force were seven transports carrying the 1st Marine Aviation Engineer Regiment, the U.S. Army's 182nd Infantry (National Guard) Regiment and supplies to sustain the forces on the island. Turner had a very potent escort: heavy cruisers Portland and San Francisco, light cruisers Helena, Atlanta and Juneau, plus nine destroyers. Turner move his forces in two separate moves, first the Engineers on three transports, with Atlanta and three destroyers as escorts, under command of Rear-Admiral Norman C. Scott, victor at Cape Esperance. Turner himself would take the rest of the forces, with his escorts under command of Rear-Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, former Chief-of-Staff to Admiral Ghormley.

Halsey had an advantage: advance knowledge from COMINT of Japanese plans. He realized that every US gain to that point was at stake. But he could only get a third of his forces underway in time. Enterprise and her screen, augmented by heavy cruiser Pensacola, departed Nouméa; but they would not arrive in time to stop the Japanese. Admiral Turner's transports reached Guadalcanal in the early hours of 12 November, and commenced unloading rapidly.

The evening of November 12, Turner withdrew his transports with a weak escort force and left the area. He left behind a force combining Admiral Callaghan's forces with those of Admiral Scott, under command of Callaghan, who was two weeks senior to Scott, who had been victorious in the surface engagement at Cape Esperance a month earlier. This may have been a bad choice. Callaghan had no combat experience and no experience or understanding of radar. What he did have was courage.

About 0130 on November 13, Callaghan's force of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers and eight destroyers stumbled across Abe's force of two battleships, a light cruiser and thirteen destroyers.

In a confused and brutal night engagement, both Admiral Scott and Admiral Callaghan died in battle (Scott possibly from USS San Francisco's friendly fire), the US Navy lost two light cruisers and four destroyers. Admiral Abe lost one battleship (Hiei), two destroyers and seven transports.

Japan did not succeed in landing reinforcements.

But the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was not yet over.

Japan had achieved major successes against the US Navy, including submarine attacks on USS Saratoga and battleship North Carolina, under repair at Pearl Harbor. In late October, Japan sank the carrier USS Hornet and thought they might have sunk Enterprise. Now they planned to send a powerful surface force to bombard Henderson Field, where the "Cactus Air Force" of Marine, Navy and Army aircraft continued to operate with deadly effect against Japanese naval forces trying to reinforce Guadalcanal.

The night of November 12/13, 1942, the Japanese bombardment force under Admiral Abe approached the area, passing south of Savo Island, with two battleships, a light cruiser and thirteen escorting destroyers. The battleships were armed with high explosive projectiles to do maximum damage against the aircraft and fuel dumps at Henderson Field. Such projectiles would be of limited use against battleships and heavy cruisers, but Abe expected no opposition.

The Enterprise had not been sunk. She was undergoing urgent repair at the harbor of Noumea. Her formation was still a powerful force: the fast battleships Washington and South Dakota, the heavy cruiser Northampton, the light cruiser San Diego and six destroyers were protecting her.

At Espiritou Santo, moreover, Halsey retained Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner's transport units, to conduct another supply run to be completed by 12 November. In his force were seven transports carrying the 1st Marine Aviation Engineer Regiment, the U.S. Army's 182nd Infantry (National Guard) Regiment and supplies to sustain the forces on the island. Turner had a very potent escort: heavy cruisers Portland and San Francisco, light cruisers Helena, Atlanta and Juneau, plus nine destroyers. Turner move his forces in two separate moves, first the Engineers on three transports, with Atlanta and three destroyers as escorts, under command of Rear-Admiral Norman C. Scott, victor at Cape Esperance. Turner himself would take the rest of the forces, with his escorts under command of Rear-Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, former Chief-of-Staff to Admiral Ghormley.

Halsey had an advantage: advance knowledge from COMINT of Japanese plans. He realized that every US gain to that point was at stake. But he could only get a third of his forces underway in time. Enterprise and her screen, augmented by heavy cruiser Pensacola, departed Nouméa; but they would not arrive in time to stop the Japanese. Admiral Turner's transports reached Guadalcanal in the early hours of 12 November, and commenced unloading rapidly.

The evening of November 12, Turner withdrew his transports with a weak escort force and left the area. He left behind a force combining Admiral Callaghan's forces with those of Admiral Scott, under command of Callaghan, who was two weeks senior to Scott, who had been victorious in the surface engagement at Cape Esperance a month earlier. This may have been a bad choice. Callaghan had no combat experience and no experience or understanding of radar. What he did have was courage.

About 0130 on November 13, Callaghan's force of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers and eight destroyers stumbled across Abe's force of two battleships, a light cruiser and thirteen destroyers.

In a confused and brutal night engagement, both Admiral Scott and Admiral Callaghan died in battle (Scott possibly from USS San Francisco's friendly fire), the US Navy lost two light cruisers and four destroyers. Admiral Abe lost one battleship (Hiei), two destroyers and seven transports.

Japan did not succeed in landing reinforcements.

But the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was not yet over.

Sunday, November 11, 2012

Seventy Years Ago: Southwest Pacific - Noumea

November 11, 1942. USS Enterprise, under repair at Noumea, gets underway with repair crews from the tender Vestal still on board. Assisting in repairs was a 75-man detachment of Seabees.

The commanding officer of Enterprise, Captain Osborne Bennett "Ozzie B" "Oby" Hardison, USN (USNA- Class 1916, North Carolina) reported to the Navy Department that "The emergency repairs accomplished by this skillful, well-trained, and enthusiastically energetic force have placed this vessel in condition for further action against the enemy." That was a matter of opinion, though her crew had no doubts.

Enterprise, damaged though she was, was the only remaining operational carrier in the Pacific. As she headed for more combat, a fuel tank was leaking, her watertight integrity was compromised, and one aircraft elevator was still jammed from bomb damage from October 26. The flight deck crew posted a sign: "Enterprise vs. Japan."

The commanding officer of Enterprise, Captain Osborne Bennett "Ozzie B" "Oby" Hardison, USN (USNA- Class 1916, North Carolina) reported to the Navy Department that "The emergency repairs accomplished by this skillful, well-trained, and enthusiastically energetic force have placed this vessel in condition for further action against the enemy." That was a matter of opinion, though her crew had no doubts.

Enterprise, damaged though she was, was the only remaining operational carrier in the Pacific. As she headed for more combat, a fuel tank was leaking, her watertight integrity was compromised, and one aircraft elevator was still jammed from bomb damage from October 26. The flight deck crew posted a sign: "Enterprise vs. Japan."

Thursday, November 1, 2012

The Greatest Generation?

Tom Brokaw called the generation who lived through the depression and fought World War II "the greatest generation."

I wish he hadn't.

They accomplished amazing things, but they weren't the greatest.

The greatest generation were their leaders. Born in the 19th Century, inspired by the Civil War Generation but determined to do better, forged on the anvil of World War I. Admirals Leahy, Nimitz, King, Halsey, Kimmel (who might have been great); Generals Vandegrift (USMC), Marshall, Eisenhower, Bradley, MacArthur,Hap Arnold, Doolittle. This was the generation who completed the design of the profession of arms that was set in motion by the likes of Mahan.

Equally important were the civilian leaders who matured in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influenced by America's move out into the world after the Civil War. They found it perfectly natural that America should be involved in China, Russia, Europe, and Latin America. They were schooled for it and accustomed to it. Men like Roosevelt, Hull, Knox, Stimson and others.

But wars rightfully belong not to those who plan them and lead them, the strategists, but to the GI's. The grunts. The sailors, soldiers and young officers who led them into battle, often with little idea of the aim of their effort beyond the next hill, the next ship or plane encountered, or the target in their periscope.

They are the ones who have to make it work.

Both groups are essential, but the generals and admirals can plan in perpetuity. If the soldiers and sailors can't make it happen, it won't.

My look at World War II has concentrated on the naval war in the Pacific. Surface warships are what I know best. But I am also fascinated by the inter service cooperation throughout the war. Cooperation between Navy and Marine Corps is not surprising. Marines have been proud to call themselves "soldiers of the sea," and they belong to the Department of the Navy.

But we forget how closely the Navy and Army cooperated during the war. Not only in the Doolittle raid. The Army was involved in Guadalcanal. The services worked together to invade Normandy. Army aircraft flew from Navy aircraft carriers from as early as May, 1941 to the end of the war. Army aviators used the Norden bombsight, designed by and for the Navy. The Navy flew B-24's and other planes designed for the Army. In the Southwest Pacific, Army pilots attacked ships with Navy torpedoes fitted to their B-26's. The Navy evacuated MacArthur from Corregidor.

This was cooperation, not competition. OK, there might have been a bit of friendly competition. Like the Army-Navy game. But when there was a job to do, they did it together.

Sailors know some things civilians don't grasp. They know they are all in this together. If a ship sinks, everyone goes down with it. Even if one survives, he has lost shipmates, his home, and the ship itself, which is more than just a floating steel box. It is, for as long as sailors are aboard, the center of their lives and the core of the most intense experience they will ever have. A shared experience.

Each sailor depends on his shipmates for his very survival. If the electrician's mate doesn't keep up the batteries in the battle lanterns, men won't be able to find their way when battle damage destroys the electrical distribution system and the lights go out.

If the Water King (usually a first class petty officer) lets boiler water chemistry get out of tolerance, a boiler tube might fail, killing shipmates operating the boiler. It could slow the ship and bring it under attack. If the radar operator isn't vigilant, an enemy ship or plane might attack without warning.

It isn't about rugged individualism. It is about working together.

And none of it is for profit.

I wish he hadn't.

They accomplished amazing things, but they weren't the greatest.

The greatest generation were their leaders. Born in the 19th Century, inspired by the Civil War Generation but determined to do better, forged on the anvil of World War I. Admirals Leahy, Nimitz, King, Halsey, Kimmel (who might have been great); Generals Vandegrift (USMC), Marshall, Eisenhower, Bradley, MacArthur,Hap Arnold, Doolittle. This was the generation who completed the design of the profession of arms that was set in motion by the likes of Mahan.

Equally important were the civilian leaders who matured in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influenced by America's move out into the world after the Civil War. They found it perfectly natural that America should be involved in China, Russia, Europe, and Latin America. They were schooled for it and accustomed to it. Men like Roosevelt, Hull, Knox, Stimson and others.

But wars rightfully belong not to those who plan them and lead them, the strategists, but to the GI's. The grunts. The sailors, soldiers and young officers who led them into battle, often with little idea of the aim of their effort beyond the next hill, the next ship or plane encountered, or the target in their periscope.

They are the ones who have to make it work.

Both groups are essential, but the generals and admirals can plan in perpetuity. If the soldiers and sailors can't make it happen, it won't.

My look at World War II has concentrated on the naval war in the Pacific. Surface warships are what I know best. But I am also fascinated by the inter service cooperation throughout the war. Cooperation between Navy and Marine Corps is not surprising. Marines have been proud to call themselves "soldiers of the sea," and they belong to the Department of the Navy.

But we forget how closely the Navy and Army cooperated during the war. Not only in the Doolittle raid. The Army was involved in Guadalcanal. The services worked together to invade Normandy. Army aircraft flew from Navy aircraft carriers from as early as May, 1941 to the end of the war. Army aviators used the Norden bombsight, designed by and for the Navy. The Navy flew B-24's and other planes designed for the Army. In the Southwest Pacific, Army pilots attacked ships with Navy torpedoes fitted to their B-26's. The Navy evacuated MacArthur from Corregidor.

This was cooperation, not competition. OK, there might have been a bit of friendly competition. Like the Army-Navy game. But when there was a job to do, they did it together.

Sailors know some things civilians don't grasp. They know they are all in this together. If a ship sinks, everyone goes down with it. Even if one survives, he has lost shipmates, his home, and the ship itself, which is more than just a floating steel box. It is, for as long as sailors are aboard, the center of their lives and the core of the most intense experience they will ever have. A shared experience.

Each sailor depends on his shipmates for his very survival. If the electrician's mate doesn't keep up the batteries in the battle lanterns, men won't be able to find their way when battle damage destroys the electrical distribution system and the lights go out.

If the Water King (usually a first class petty officer) lets boiler water chemistry get out of tolerance, a boiler tube might fail, killing shipmates operating the boiler. It could slow the ship and bring it under attack. If the radar operator isn't vigilant, an enemy ship or plane might attack without warning.

It isn't about rugged individualism. It is about working together.

And none of it is for profit.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Loss of USS Hornet (CV-8) October 26 1942

I have been reading as many accounts of Hornet's sinking as I can find.

I keep wondering exactly why the ship was abandoned. Her sister ship, Yorktown, was lost at the Battle of Midway because of progressive flooding and loss of electrical power to drive the dewatering pumps. Yorktown reached a maximum list of 24 degrees before the decision to abandon ship the day after the battle at Midway. But Captain Buckmaster intended to put a salvage crew back aboard the following day.

I also learned from reading Yorktown's loss report that loss of electrical power was apparently due to the ship's electricians setting up the electrical switchboards in parallel. This meant that when torpedo damage destroyed the forward switchboard and killed the electricians in that space, the after switchboard shorted out whenever the emergency diesel generator tried to come on line. That's why electrical power was lost.

Long experience with damaged capital ships, going back to the bombing experiments promoted by Army Air Corps General Billy Mitchell, made it plain that slow progressive flooding was survivable with a crew aboard well trained and equipped for damage control.

To abandon ship prematurely was a death sentence (for the ship).

But I can find no evidence that Hornet had progressive flooding, even after the second Japanese air attack. The damage report here suggests the ship was on the verge of getting her steam propulsion plant back into operation.The ship's list never exceeded 14 degrees.

After the ship was abandoned, US destroyers tried to sink the ship with more than 500 rounds of 5-inch ammunition and with torpedoes without success.

The empty, blazing vessel was finally left adrift. Japanese navy ships attempted to take Hornet under tow and finally sank her with two large Japanese Long Lance torpedoes.

I also wonder why USS Enterprise, still in the vicinity and able to operate aircraft despite damage, didn't do a better job of protecting Hornet against Japanese air attacks.